Centenary Radio: WJR – The Goodwill Station

[May 2022] Spring 1922 saw major growth for Radio with an explosion of stations. It is always interesting to see those that have survived for the century, sometimes with a three-letter call intact. WJR in Detroit is one of those stations, growing from a shakey beginning in 1922 to become a 50,000 Watt Flamethrower and a well-known, familiar brand where the Motor City turns to get news and information.

Broadcasting in the early 1920s was not a secure profession. As with any new product or Industry, the pioneering stations had a high rate of attrition.

Some if them found the costs of operation too high or suffered from mismanagement. Others were unable to get enough airtime during the years when all the stations were packed onto just a few channels. And some owners just lost interest.

Eventually, in 1928, the Federal Radio Commission (FRC) pruned the list of licenses and deleted several hundred stations deemed not to be broadcasting in “the public interest, convenience and necessity.”

A Shakey Start

The birth of WJR radio was afflicted with several of these problems

Although a 50 kW powerhouse today in Detroit, with a long history of service to the community, the station barely survived its first years.

Even getting started was not easy. Building a legendary brand in the broadcast industry was not what E. D. Stair, owner of the Detroit Free Press, had in mind.

Stair reluctantly permitted his General Manager W.H. Pettibone to start a radio station to meet the competition from WWJ, the Detroit News station. In his mind, WWJ Radio was little more than a frill; Stair was skeptical it would ever amount to very much, so he did not expect much from Pettibone’s idea, either.

On The Air

Early 1922 saw an explosion of radio stations, as many companies and religious organizations sought to get in at the start of the new industry.

The Free Press station, WCX, Pontiac, MI (a suburb of Detroit) debuted on May 4, 1922 with impressive sign-on ceremonies that were typical for the pioneer stations of the time, including comments from the Governor, the University President, and other local dignitaries and a variety of musicians, singers, and other performers.

Reception reports came in by telegram and letter from many cities, some as far away as Texas and Arkansas. However, Stair still was not impressed.

Many engineers today will instantly guess one big reason why that happened: despite all the places where the station could be heard loudly and clearly – including on the telephones of local residents – one of the few “dead spots” just happened to be the area near the Belle Isle Bridge – yes – the location of Stair’s home!

Apples and Listeners

Getting talent was another big difficulty.

The local theater owners quickly decided radio was a competitive threat and kept many professional artists from appearing on WCX. Long periods of silence did not help the station attract listeners.

The staff did persevere, searching for ways to find and develop a listening audience. Station Manager Neal Tomy did his best, guiding the station move to 580 kHz in 1923 and then devising a contest to see how much of an audience was really out there.

A WCX EKKO stamp

A “Michigan Red Apple” was offered to the first listener who identified a particular singer. So many responses arrived that WCX decided to organize the “Red Apple Club” – which grew to a half-million members in less than a year.

Nevertheless, Stair still was not impressed, even by the bags and bags of fan mail. He chafed at the $15,000 it took to operate the station for the year. WCX had seemed unable to attract much advertising, and most of its programs had run unsponsored.

A Very Shakey Merger

Thus Stair was very interested when his friend, Edward Jewett, offered a proposition.

Jewett’s new station, WJR (Jewett Radio) would provide a new transmitter and $75,000 a year in financing if the two stations would share facilities. The combined WJR-WCX premiered on August 16, 1925, the second station (after WLW) to go “superpower” at 5,000 Watts.

Unfortunately, Jewett was not a very good owner/manager, and financial crises arose almost immediately. With Stair unwilling to put in any additional monies, the station came to the brink of financial collapse in March of 1926.

Out of the Ashes

The future looked very bleak at WJR-WCX. Jewett Radio was to be liquidated.

Yet, out of this disaster the station rose to success under the leadership of the man hired to dismantle the broadcast station, Leo Fitzpatrick.

Fitzpatrick had come to WJR from the successful WDAF program “Kansas City Nighthawks.” The “Merry Old Chief” was determined to make WJR-WCX successful. He convinced the liquidator to allow him time to try.

Among his first actions, Fitzpatrick had the station’s antenna re-oriented more toward Detroit.

With an improved signal, attention then was given to finances. Advertising was still a rather hard sell to many businesses, which were slow to appreciate the intangible nature of radio advertising. Fitzpatrick came up with the idea of selling sponsorship announcements tied to the station IDs. It turned out to be very successful.

Among those in whom Fitzpatrick found an appreciation of the power of radio – and ready to pay full commercial rates – were several local churches. One of these sponsors was destined to become one of the most famous, controversial, and most reviled of all broadcasters: “Father” Charles Coughlin.

The turnaround came very quickly. After just one month, WJR was operating with a monthly profit.

The turnaround came very quickly. After just one month, WJR was operating with a monthly profit.

And that success attracted the attention of one of the station’s major sponsors: G.A. Richards.

The Goodwill Station

Noting the prestige and good will his Oakland and Pontiac automobile dealerships got from his association with WJR, Richards decided to option, and then purchase. the station,

With Richards’ money and flair for showmanship, WJR, which he dubbed “The Goodwill Station” was quickly established as a major factor in the market.

With Richards’ money and flair for showmanship, WJR, which he dubbed “The Goodwill Station” was quickly established as a major factor in the market.

New studios were built, NBC’s Blue Network was picked up, and special broadcasts were put on to show the immediacy and importance of radio.

Even the FRC helped by permitting WJR-WCX to move to 680 kHz, then later to 750 kHz, during part of the National Frequency Change on November 11, 1928. Best of all, WJR-WCX was now all alone on that channel.

The strategy worked. Even the theater owners took note and began permitting remote broadcasts right from their stages.

WJR prospered so much that Richards retired from the automobile business to devote himself to radio. He shared the station’s prosperity, annually granting generous bonuses to the staff.

Then new studios and offices were built in the brand new Fisher Building and “From the Golden Tower of the Fisher Building” became a common on-air slogan.

Soon Richards offered to buy out WCX. This delighted E. D. Stair, who had never liked radio in the first place.

And with that, WCX just faded away in early 1929.

Making Radio and Business Waves

By contrast, WJR continued to grow.

The Depression made entertainment broadcasts on radio ever more important to many people. Listeners came to expect news as another essential service so WJR began to develop a greater news image, including interviewing newsmakers on the air. Live musical programs were also a station staple, well into the 1970s.

In the 1930’s, the tightening financial situation as the Depression deepened. According to the New York Telegram, every 50,000 Watt station in the country ended 1929 in deficit. In contrast, G.A. Richards decided to increase WJR’s power to 10,000 Watts, mainly to protect their clear channel status.

Although the transmitter site was moved 31 miles out into the country-side, two years later the station officially changed its “City of License” to Detroit.

Then, a 1935 fight with NBC over compensation led to a change in affiliation. Simultaneously with the inauguration of a new 50,000 Watt transmitter, WJR changed to the CBS radio net-work on September 29, 1935.

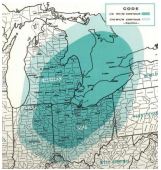

WJR puts its primary signal over parts of five states

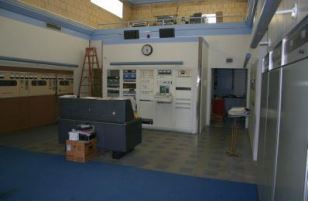

WJR’s Transmitter Control with its new

50 kW Western Electric 407 transmitter.

Of course, it was not all easy, in November of 1940, heavy winds knocked over the station’s 733-foot tower. It was replaced with a slightly shorter, 700-foot tower.

One more “change of address” occurred as part of the National Frequency Move in March 1941. The station moved up 10 kHz, bringing WJR to its current location at 760 kHz.

Among the many talented behind-the-scenes individuals who came to WJR during the 1940s was James Quello. Quello rose from promotion and publicity director to Program Director, Vice President, General Manager, and eventually he even became an FCC Commissioner.

An Honored Station

WJR continued to run CBS programming, even originating some of it in-house, including the Ford Sunday Evening Hour, which ran coast-to-coast.

Many of WJR’s programs and talent were honored with various awards. The continued emphasis on quality programming led to a long list of awards won by the station, culminating with three prestigious awards in 1996.

The General Manager at the time, Mike Fezzey, expressed great pride over the industry recognition that year, especially the World Media Expo naming WJR a “Legendary Station.”

“I don’t know of another station that has been named Legendary Station of the Year, as well as receiving the Edward R. Murrow Award and the Peabody Award, all in one year,” Fezzey said. “I believe this speaks great volumes to the tradition of excellence at WJR.”

Fezzey remarked “the great challenge we have now is to adapt to the various cultural changes in the Detroit market so that we can be sure to meet the needs and expectations of our listeners.”

From the 20th to the 22nd Century

Indeed there were a number of changes coming, and WJR would be adapting as time passed.

The desire to ensure the best possible programming occasionally led WJR to more disagreements with the national networks over the years. But as it was highly rated, the networks allowed WJR latitude that no other stations got at that time.

G.A. Richards passed away in 1951, but his family continued to operate WJR until it was acquired from the Richards estate in 1964 by Capital Cities.

As television grew in the 1950s, the radio industry underwent major changes, and WJR had to work hard to stay at the top of its game. As part of the merger of CapCities and ABC in 1985, the network affiliation was changed.

CapCities/ABC/Disney operated the station for 42 years, selling it to Citadel Comm. in January 2006. In September 2011 Citadel merged into Cumulus Media, the current ownership.

WJR Master Control in 1964

The new WJR Master Control in 2006

WJR’s Transmitter Hall, with a DX-50 main,

and 317-C2 and MW-50 backups

WJR continues to serve the Detroit market with a news and talk format. Over five decades, WJR changed as the industry changed, slowly shifting from a Full Service station to a News-Sports-Talk format. More recently the emphasis is on the Talk format, both local and satellite deliver-ed, along with a reworked Sports presentation.

In 2006, the station even built a studio in the Renaissance Tower in the middle of downtown Detroit, to provide easy access for interviewing local celebrities and sports figures. During the daytime, for example, Paul W. Smith, Frank Beckmann and Mitch Albom shared time with the late Rush Limbaugh.

Now 100 years down the line from the tiny seeds at WCX, “The Great Voice of the Great Lakes” continues to sport the WJR call letters and presents its strong image in the local community.

Over the past few months, WJR has presented a number of audio clips and other memories to celebrate the station’s history. You can find these items here.

– – –

If you enjoy Radio History, we invite you to subscribe to the one-time-a-week BDR Newsletter.

Please take just 30 seconds, sign up here, and you will know when more articles are posted.