Centenary Radio: WABC – A NYC Pioneer Crosses the 100-Year Line

[October 2021] We continue our series of stations reaching the century mark of service with WABC.

While the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company did not own all of the pioneering radio stations that made their debut in 1920-1921, they certainly owned a majority of them.

We have already discussed KDKA in Pittsburgh, and WBZ in Springfield, MA. Now, let us take a closer look at another Westinghouse station: WJZ in Newark, New Jersey.

FIRST IN NEW JERSEY

WJZ made its official debut on October 1, 1921, after several months of test broadcasts.

Sporting a Department of Commerce license, #230, this was the third Westinghouse station to begin regular broadcasts to the public. If you were a reader of the Newark Sunday Call, you saw the story of the new station’s debut prominently displayed on Page 1 of the paper’s October 2nd edition.

That front page coverage was not entirely accidental: the Call had entered into an agreement with Westinghouse to collaborate on operating the new station. The Call also began providing a weekly radio page, with information about the performers and the programs on the new station.

Not all newspapers were so enthusiastic about radio, however: while 8MK (later WWJ) in Detroit was owned and operated by the Detroit News, and a few other early stations, including 1XE (later WGI) in Medford Hillside collaborated with a local newspaper to get news headlines, other stations would have a more contentious relationship with the print industry.

As more new radio stations came on the air in 1922, some newspaper editors decided that the new mass medium was a threat; they believed (erroneously) that if people had a radio, they would no longer buy a newspapers. And so, they decided not to mention that their city was getting its own station.

COOPERATION

But that was not the case in Newark, nor in much of the New York/New Jersey area.

Many newspapers carried the Westinghouse press releases about WJZ, and the Newark Sunday Call did its part to promote the station. Magazines like Radio News praised the “progressive” attitude of the Call; editor Hugo Gernsback praised the newspaper’s thorough radio coverage.

He also praised WJZ, noting that in its first few weeks on the air, it was already offering listeners a wide range of musical selections from jazz to opera, as well as educational talks, and bedtime stories for children from “The Man in the Moon.” And the signal could be heard “within a radius of several hundred miles.” Gernsback was so interested in what WJZ was doing that he devoted several pages of the December 1921 edition of Radio News to an in-depth look at the station’s accomplishments.

BRINGING THE STUDIO DOWN

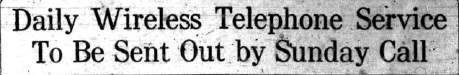

WJZ’s first studio was located on the roof of the Westinghouse factory, at the intersection of Plane and Orange Streets in Newark.

But it was not long before it was found necessary to build a new studio on the first floor of the building. This made it much easier for the various performers on WJZ to access the studio.

The WJZ Studio on the First Floor

The performances were all live (audiotape had not been invented, nor had electrical transcriptions), and in addition to the musical programs and educational talks, there were daily news reports and a roundup of sports headlines from the Call.

TECHNICAL OPERATIONS

The new station’s frequency, assigned by the Department of Commerce, was 360 meters (about 833 kHz), as all in 1921.

At first, WJZ was on the air several nights a week, but by year’s end, the station had expanded to offer programs every week night, and by early 1922, there were educational and religious programs on Sunday afternoons.

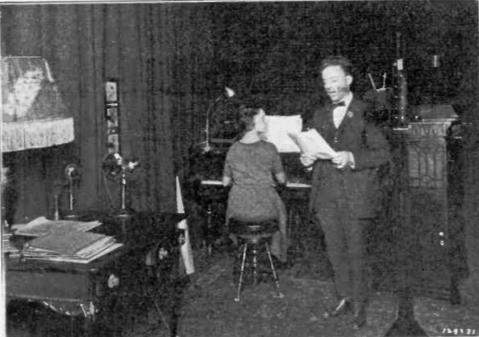

WJZ used a 500 Watt transmitter, identical to the one built for KDKA.

WJZ’s 500 Watt transmitter 1921

In fact, the Sunday Call noted that Frank Conrad of KDKA came to Newark prior to WJZ’s first program, to inspect the equipment and make sure everything was operating properly.

IS IT LIVE OR … ?

Early October 1921 turned out to be an excellent time to put a new radio station on the air, because the World Series was going on, and listeners were able to enjoy the ballgame between the New York Giants and the New York Yankees from the comfort of their own home.

The press releases from Westinghouse gave the impression that WJZ would provide live play-by-play from the Polo Grounds in New York City, on the afternoon of October 5th. Evidence suggests, however, that WJZ announcer Tommy Cowan did a recreation, using reports that were sent by telephone from the ballpark by the Sunday Call’s Harry Nash to the WJZ rooftop studio. (In fairness, the Call was more honest about what was being planned, acknowledging that reports from the game would be “relayed from the Polo Grounds… to the operating booth on the roof of the Orange Street works…”)

Given that there was nothing to compare it to, the listeners were undoubtedly delighted by how the broadcast sounded; and Cowan was undoubtedly relieved he got through it. (It is also unclear if listeners even knew who was broadcasting the game: in those early days, announcers were identified by a set of initials rather than by their name. Cowan was ACN, or Announcer Cowan Newark.)

MUSIC IN THE AIR

WJZ quickly established itself as a place where listeners could hear some of the biggest names in music.

In the first few weeks on the air, the station featured numerous popular entertainers, including vocal duo Billy Jones and Ernie Hare (best known as the “Happiness Boys”), recording artists the Shannon Four, and opera star Maria Rappold.

Then, in early 1922, WJZ experimented with broadcasting a Broadway play—the Broadway musical comedy “The Perfect Fool.” The cast, including its star Ed Wynn, came to WJZ on February 19, 1922 and they performed the play in its entirety. By all accounts, Wynn found performing for the “invisible audience” very disconcerting, an emotion shared by many early performers in that era before studio audiences became the norm.

It is also worth noting that most performers on early radio were not paid, and persuading the big names to volunteer their time was not always easy. Westinghouse stations could offer a bigger signal than some of the independently owned stations, and they could also offer a massive publicity push from the Westinghouse publicity department. The fact that Ed Wynn performed on WJZ was published by newspapers from coast to coast, getting him lots of favorable attention.

OPERA AND MORE

Another interesting achievement for WJZ came on September 20, 1922, when the station broadcast the San Carlo Opera Company’s presentation of the opera “Aida,” with nationally-known soprano Maria Rappold in the lead role.

In addition to music, WJZ also gave listeners the chance to hear a wide range of interesting speakers, including Hiram P. Maxim, founder of the American Radio Relay League; New York rabbi Stephen S. Wise; author and Protestant minister Frank Crane; and motion picture executive Adolph Zukor, who reminisced about the first ten years of the movie industry.

One of the regular features that fans of WJZ came to love was “Broadcasting Broadway,” which made its debut in March 1922. Hosted by Bertha Brainard – with the on-air “handle” of ABN – she was one of the few female announcers with her own program, its focus was on the latest theatrical news.

Bertha Brainard

Brainard interviewed Broadway performers, as well as discussing some of the current plays.

TRAFFIC JAM ON THE AIR

By early 1923, WJZ was one of many stations sharing 360 meters.

And while the station could still attract high-profile talent, including bandleader Vincent Lopez and his orchestra or actress Ethel Barrymore, the airwaves were getting more crowded, and listeners were complaining about interference. Station owners were pressuring the Department of Commerce to open up more frequencies—both to allow for more airtime, and to create more listenable conditions.

In late April 1923, newspapers reported that WJZ would finally receive a new frequency by mid-May, 455 meters (660 kHz). But it was only one part of several other changes that affected the station. For one thing, WJZ was sold to the Radio Corporation of America, and for another, it was announced that the station would soon be leaving Newark for new studios in New York City, which WJZ would share with a sister station, WJY at 405 meters (740 kHz).

BROADCAST CENTRAL

The existence of a new radio facility, known as Broadcast Central, was not entirely a surprise to fans who followed New York radio closely. For the previous several weeks, there had been test broadcasts from the Broadcast Central station, using the experimental call letters 2XR, but until now, there had not been much information about its plans.

The new, state-of-the-art studios were located on the sixth floor at Aeolian Hall, on West 42nd Street. The May 12, 1923 issue of Radio Digest referred to Broadcast Central as a “super-station,” noting that it not only had two studios and two independent transmitters but its “wires… tower 400 feet above the Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street [venue], and provide two distinct antennae.” In addition, the main recital hall, on the ground floor of the venue had also been fitted for broadcasting.

The new studios and transmitters officially went on the air on May 15, and WJZ transitioned from saying “This is station WJZ, Newark, New Jersey” to saying, “This is Station WJZ, Radio Broadcast Central, at Aeolian Hall, New York City.”

PROGRAM DIRECTION

One person who was very pleased with the move was Bertha Brainard, since she would now be closer to the Broadway venues and entertainers she covered during her show.

By mid-1923, she was not just one of the few women announcers; she was also one of the few women in management, having been promoted to WJZ’s assistant program director by program director Charles Popenoe.

In addition to establishing a program for homemakers, Brainard also auditioned some of the entertainers who wanted to be on the air, and she helped to choose the ones who would perform.

Another influential figure at WJZ was Milton J. Cross, who began his radio career as a vocalist. He was a tenor, and he had performed on the station since its earliest days; in fact, he continued to perform now and then well into the late 1920s.

Milton J. Cross aka AJN

But in the mid-1920s, he began doing some announcing for WJZ, and by late 1926, he had risen to the station’s chief announcer; the audience loved his voice, and he received fan mail from all over the United States.

One other popular “regular” on WJZ was a singer named Alma Kitchell. Born Alma Hopkins, the popular contralto could be heard on New York radio stations WEAF, WJY and WJZ as early as 1923-24 (sources that claim her radio career began in 1927 are incorrect). By early 1926, her radio performances were so well-received that critics spoke of her as “one of the nation’s greatest soloists”; and while she occasionally broadcast for other stations in 1926, she was increasingly being heard on WJZ.

The station was also expanding its sports coverage. After starting off with a baseball re-creation in 1921, WJZ soon began offering some live play-by-play broadcasts of various sports, usually announced by Major J. Andrew White, and later by his protégé Ted Husing.

Re-creations were still around however – due to the expense of broadcasting from long distances it was the norm to re-create the away games. But by 1923-1924, many home games and local sporting events – from boxing matches to yacht races to baseball and college football games – were broadcast live.)

RAISING POWER

And if you were looking for WJZ on your radio dial, it was usually at 660 kc (newspapers and magazines tended to refer to “kilocycles” back then).

During the mid-1920s, WJZ, along with a small group of other key stations (including KDKA), received permission from the Department of Commerce to broadcast at higher power, a strategy meant to improve reception in some of the more congested radio markets.

In late 1925, WJZ got the go-ahead to transmit with 50,000 Watts – a far cry from the 1000 Watts it had used in 1923/24. WJZ also got a new transmitter site, in Bound Brook, New Jersey, about 35 miles from New York City.

While WJZ’s many fans were probably pleased with the improved reception, not everyone was so happy. Residents of some of the towns near Bound Brook found that WJZ was drowning out all the other stations, and they complained to their representatives. Executives from RCA assured them that the newer radio receivers being developed would not have this problem.

But by mid-1926, WJZ was ordered to reduce its power slightly, to 30,000 Watts, while various engineers tried to solve the problem.

PART OF THE NBC FAMILY

In mid-November 1926, WJZ got yet another new parent company: the newly-created National Broadcasting Company.

NBC debuted on November 15th, with New York’s WEAF as its flagship station. Then, in early January 1927, a second NBC network went on the air, and its flagship station was WJZ.

To differentiate the two broadcast networks – or “chains” as they were called – the one originating from WEAF was known as the NBC Red Network, and the one from WJZ became known as the NBC Blue Network (in addition to WJZ, the chain included WBZ (Springfield, MA. and Boston), KDKA in Pittsburgh, and KYW in Chicago).

But having broadcasting chains was not the only big change in the radio landscape.

COMMERICAL RADIO TAKES OFF

In 1927, there was a new agency, the Federal Radio Commission, and a new attitude about broadcasting commercials.

Under the Department of Commerce, then-secretary Herbert Hoover had famously opposed “direct advertising,” but gradually, he relented, as owners needed a way to pay the bills (and pay for talent). By the time the new networks (the National Broadcasting Company in late 1926 and then the Columbia Broadcasting System in late 1927) were up and running, commercial advertising was a fact of life.

The revenue generated by the sponsors helped to pay for some of the biggest names, and made some of the most popular radio shows possible. It was not cheap – by early 1928, advertisers could purchase one hour of airtime on the Blue Network for $2,800; the Red Network, which had a stronger lineup of stations and programs, charged $3,770. (It was not all profit. AT&T charged as much as $4.50 per mile per hour.)

Soon, if you were listening to WJZ and the Blue Network in the late 1920s, you would have heard a large number of sponsored variety programs: among them were the Philco Hour (which debuted in early April 1927 and featured a wide range of musical talent); the Maxwell House Hour with bandleader Nathaniel Shilkret; and the Brunswick Hour (many of the artists on the program recorded for Brunswick Records). Among the most popular programs on WJZ was one that had debuted back in 1923 on WEAF, live from the Capitol Theater in New York: “Roxy and his Gang.” Hosted by theatrical impresario Samuel “Roxy” Rothafel, the show joined WJZ and NBC Blue in early 1927, to great acclaim.

MOVING DAY 1928

In November 1928, when the Federal Radio Commission assigned new frequencies to many U.S. stations, WJZ was moved from 660 to 760 on the dial.

The new assignments caused some consternation at WGY in Schenectady; the General Electric station, assigned to 790 (shared with KGO in Oakland) wanted its own “cleared channel” frequency – 760. The FRC ended up allowing WJZ to stay put, but did allow WGY to operate full-time at 790 without sharing time with KGO after all.

Studios moved to a new location as well. As the broadcast day continued to expand, and more elaborate live programs (often with a studio audience) were being presented, NBC began construction of a new broadcast operation at 55th and Fifth Avenue. When finished, it would have eight studios, and an auditorium with sufficient capacity for an orchestra of 150 musicians, as well as an equally large studio audience. That new building, at 711 Fifth Avenue, became WJZ’s home in October 1927.

ATTENTION TO PROGRAMMING

Meanwhile, Charles Popenoe, the former WJZ program director was promoted to an executive position with NBC, and Bertha Brainard became WJZ’s program director. She was not finished moving up: her ability to identify good talent caught the attention of executives at NBC, and by 1928, she was NBC’s Eastern Program Director, overseeing both WEAF and WJZ.

One program which earned WJZ a lot of praise was the Saturday afternoon Metropolitan Opera broadcast. This weekly program began in late December 1931, with chief announcer Milton J. Cross as the host. Cross was not only popular with the audience; he was also praised by professors and public speakers for having excellent diction. In fact, he was given several awards for his on-air work. He became known as the “Voice of the Met,” announcing their broadcasts for more than four decades.

WJZ and the Blue Network also was where listeners could hear news reporter Lowell Thomas, as radio news was beginning to gain more importance during the 1930s. And WJZ became known for introducing new dramatic and comedy features: in late 1929, “The Rise of the Goldbergs,” starring Gertrude Berg, made its debut, a show we today would call a “dramedy.” It went on to become one of radio’s most beloved programs, “The Goldbergs,” as it later came to be known, was a show that Bertha Brainard championed.

Brainard also promoted radio crooner and orchestra leader Rudy Vallee, who began hosting the Fleischmann’s Yeast Hour on WEAF and NBC’s Red Network beginning in late 1929.

POPULAR WITH SOME, NOT ALL

And there was one WJZ/Blue Network program which brought large audiences but also generated some controversy: “Amos ‘n’ Andy.”

The comedy program about two Black men who came to the big city (originally Chicago, later Harlem) to seek their fortune, was originally called “Sam ‘n’ Henry” when it first aired in Chicago in the mid-1920s. By the time it debuted on NBC Blue in mid-August 1929, it was known as “Amos ‘n’ Andy.”

The two Black characters were portrayed by Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, two white men in blackface – a custom popularized in minstrel shows and on the vaudeville stage.

Most critics and a large majority of the audience found the show charming and amusing, as the characters, owners of the Fresh Air Taxi Company, dealt with various problems (often of their own making) and got themselves in and out of trouble. By 1930-1931, when the first ratings surveys were issued, “Amos ‘n’ Andy” was the most listened-to program on radio.

But not all the Black listeners were happy about the show. Some, including Robert Vann, the Editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, found “Amos ‘n’ Andy” patronizing and stereotypical, depicting Black people as gullible dupes and buffoons.

Vann launched a petition drive to get the show removed from the air, but he was unsuccessful, and “Amos ‘n’ Andy” continued to be popular throughout much of the 1930s.

GETTING UP TO 50 KW

While the 1925-1926 experiment with 50,000 Watts had not worked out, WJZ’s management never gave up on the idea.

The state of the art in technology had continued to change (and improve), and in July 1930, the station’s engineers asked the Federal Radio Commission for permission to install a new transmitter. Their application stated that a new and more modern transmitter would provide better reception.

Meanwhile, in mid-September, WJZ requested the FRC allow the station to return to 50,000 Watts and broadcast at 760 kHz. On October 1, 1931, the FRC turned down the station’s request. It would not be until the summer of 1935 when WJZ was finally allowed to return to using 50,000 Watts.

WJZ finally got permission to go up to

50 kW with an RCA 50B, like KFI’s

But before that happened, WJZ, WEAF, and NBC’s corporate offices moved yet again, as NBC opened its opulent Radio City studios at 30 Rockefeller Plaza in November 1933. When all the construction was completed, it would contain thirty-five broadcast studios, including a control room that could one day be used for television.

ENTER THE FCC

And speaking of moving, in 1941, almost every radio station did.

On March 29, per orders from the Federal Communications Commission, successor to the Federal Radio Commission, an act abbreviated as NARBA (the North American Radio Broadcasting Agreement) was implemented. More than 800 radio stations received new frequency assignments, many moving as much as 40 kHz from where they were. WJZ was among them—it was moved from 760 to 770 as a 1-A Clear Channel station. A 38-year fight ensued with KOB, which left them sharing the frequency.

In the Spring of 1936, WJZ, like a number of other stations that had see WLW rise to 500 kW, petitioned the FCC for a similar power. The FCC denied it in 1942, and WJZ was to stay at 50 kW.

But even more changes were on the horizon for WJZ and the other stations that comprised NBC Blue. The FCC, expressing concern about monopolies in broadcasting, issued a ruling in May 1940 that RCA, the parent company of both NBC Red and NBC Blue, would have to divest itself of one of its two networks – since the smaller network was NBC Blue, that was the one RCA sold off.

NEW OWNER, NEW CALLS

The flagship, WJZ, as well as the other affiliates, were ultimately sold to wealthy businessman (and founder of the Life Savers candy company) Edward J. Noble in October 1943.

The sale price was reportedly eight million dollars, and the new network was subsequently renamed the American Broadcasting Company in late 1944, although newspaper ads still referred to both the Blue Network and the American Broadcasting Company while the transition was ongoing. By mid-June 1945, the name “Blue Network” was no longer used.)

A NEW TRANSMITTER SITE

In the meantime, in June 1943, WJZ had received permission from the FCC to move both its 50,000 Watt transmitter and its 25,000 Watt auxiliary from Bound Brook, New Jersey to a new facility in Lodi, New Jersey, which was about 23 miles from New York City.

It was explained as a cost-saving move, but it was also an opportunity to repurpose the Bound Brook location exclusively for shortwave. WJZ and NBC had begun using the site for experimental shortwave broadcasts around 1930, using the call letters W3XL and W3XAL; in 1943, in the midst of World War II, the Office of War Information wanted to install four new shortwave transmitters, enabling the government to more effectively transmit to overseas locations.

The new WJZ transmitter tower was 655 feet high; the facility was located on thirty acres of former swampland. When the new transmitter was put into operation on January 2, 1944, listeners told the New York Daily News radio editor the station’s signal sounded sharper and stronger.

CHANGES OF VARIOUS KINDS

WJZ continued to broadcast popular programs throughout the war years, including “Dick Tracy,” “Lum and Abner,” “Gang Busters,” and many of the era’s popular dance orchestras, comedians and variety shows.

In addition to news programs like “The March of Time” and “America’s Town Meeting of the Air,” there were commentators like Drew Pearson and Walter Winchell.

WJZ was also the home of the Saturday evening concerts from the Boston Pops, with conductor Arthur Fiedler, as well as the Saturday afternoon Metropolitan Op-era broadcasts (Milton J. Cross was still around, and still beloved. Another veteran WJZ broad-caster, Alma Kitchell, was also still around, in charge of women’s programming for the station and the network.) And even when the golden age of radio transitioned to the television era, cutting into radio listening, WJZ remained a very popular station.

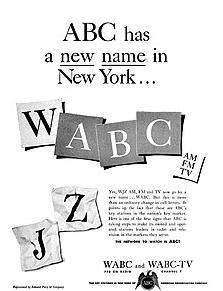

In late February 1953, ABC announced that WJZ would get a call letter change, becoming WABC. This seemed appropriate, given the station’s role as the radio network flagship, but it was undoubtedly confusing to the listeners: there had been a New York station using the call letters WABC as far back as 1926. That version of WABC (which stood for Atlantic Broadcasting Company) subsequently became a CBS affiliate, and in November 1946, its call letters were changed to WCBS.

The new WABC was announced with much fanfare and full-page ads in trade publications in early March 1953, and one of radio’s oldest sets of call letters vanished from the airwaves.

A few years later, WABC became famous again in New York and the broadcast industry as it began its reign as the dominant Top 40 station in the market until the early 1980s, when WABC transitioned to talk radio, which it has continued aside from some music shows on Saturday night.

The station was sold or merged over the years to companies like Disney and Citadel (later Cumulus), and is now locally owned by John Catsimatidis’ Red Apple Media since 2020.

TECHNICAL NOTES

Over the years, WJZ/WABC has sported some of the top transmitters in the industry.

The RCA 50B was eventually replaced in 1959 with a GE BT50A, the auxiliary transmitter was replaced with a Continental 316B.

Then in 1972 Gates/Harris MW-50As and a GE BT50A be-came Alternate Main transmitters until a pair of Harris DX50s were installed in 1999.

With 100 years under its belt since it signed on as WJZ, WABC continues to be an important part of the New York Radio Market.

– – –

Donna L. Halper is a media historian, educator (Associate Professor of Communications and Media Studies at Lesley University), and radio consultant.

She is the author of six books and many articles about the history of broadcasting. Contact her at: dlh@donnahalper.com

– – –

Did you enjoy this article? Would you like to know when more articles like this are posted? It only takes 30 seconds to sign up here for the one-time-a-week BDR Newsletter.