Centenary Radio: KYW: A Pioneer Call Sign Opens In Chicago

[November 2021] In recent years, consolidation has seen quite a few legacy call letters shifting from one facility to another. The early days of radio, a few stations themselves moved around, Sometime hundreds of miles. And one moved back … and forth.

Among all the pioneering stations in radio’s formative years, KYW, the Westinghouse station in Chicago, was unique.

In an era when most stations broadcast programs in fifteen minute increments, from a wide range of styles and genres, KYW was the first station to make use of one specific format – all-opera, featuring live performances by the Chicago Grand Opera Company. Each night, an entire opera would be broadcast, including any announcements that were given between each act. In other words, the at-home listeners would hear exactly what the audience at the venue was hearing, in real time.

Of course, there was no way to know whether broadcasting opera was a wise decision.

FINDING AN AUDIENCE

In 1921, measuring audience reaction was not possible; stations depended on fan mail, unaware that this was not a reliable way to measure, since the majority of listeners never wrote to their favorite station.

Ratings services would not be available till 1930, and as a result, claims that stations had “a hundred thousand listeners” were impossible to verify. There was also no way to know whether opera was as popular with the average Chicagoan as it was with radio columnists, members of the upper-class, and music teachers – in several high schools and universities, educators were especially pleased, because they could now expose their students to nationally-known opera stars.

What we do know is that by choosing this type of programming, KYW received a massive amount of publicity in newspapers and magazines, as well as a steady stream of fan mail from opera lovers who were delighted that they could hear the most famous performers without having to do anything more than own a radio set.

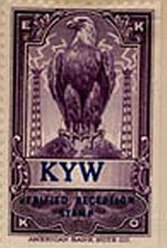

KYW Chicago

Reception Verification Stamp

American Bank Note Co.

Westinghouse’s radio division, which was known for its ability to get favorable publicity, capitalized on the positive reaction. The company’s publicist, George H. Jaspert, was very effective at calling attention to whatever KYW was doing, and newspapers from coast to coast began printing the press releases he sent out – sometimes verbatim.

GROUP W IN CHICAGO

KYW was the fourth station that Westinghouse put on the air: preceding it were WJZ, then in Newark, New Jersey; WBZ, then in Springfield, Massachusetts: and KDKA, in Pittsburgh.

Additionally, KYW was a collaboration between Westinghouse and the Commonwealth Edison Company – the station’s transmitter was located on the roof of the Commonwealth Edison Building, on West Adams Street in Chicago, with the studios on the sixteenth floor.

As with all early stations, KYW first broadcast on a wavelength of 360 meters (about 833 kilocycles). According to former Westinghouse engineer Joseph Baudino, “The transmitter consisted of two 250 Watt tubes used in a self-excited Hartley circuit, the output of which was Heising modulated by three 250 Watt tubes. The plate supply was obtained from a 2000 Volt direct current generator. The original antenna was a four-wire flat top supported by two 50-foot steel poles mounted on top of the building.”

In February 1922, Radio News profiled KYW, noting that the new station – Chicago’s first – made several test broadcasts before officially making its debut on November 11, 1921. Amateurs throughout the Midwest were notified ahead of time, so that they could “listen in” and report to their local newspapers on how opera by radio sounded.

The amateurs responded enthusiastically: not only was the transmission clear, but many who heard it expressed interest in sharing the experience with family members and neighbors.

A POPULAR SINGER

One big reason that many listeners were eager to receive KYW was the fact that Mary Garden would be performing.

Mary Garden

She was one of the best-known sopranos of her day, and the press treated her as a true celebrity. She was frequently quoted, and even people who did not like opera knew who she was. But Garden was more than just a famous opera star: she was also a savvy businesswoman.

She became the director (or as they called her back then, the “directress”) of the Chicago Grand Opera Company, one of the few women in such a position of authority. (In typical hyperbolic style, some newspapers asserted that she was “the first woman in the world” to hold this job.)

Garden proved to be forward-thinking when it came to radio: unlike some early performers who saw the new mass medium as a threat, believing (incorrectly, as it turned out) that if their performances were broadcast, fans would no longer want to see them live, Garden decided that broadcasting the opera company’s performances on KYW would generate lots of favorable publicity and increase the public’s interest in opera. She was right.

ANOTHER MYTH PUNCTURED

Newspaper articles from the 1970s and 1980s would claim that Garden’s first words on the radio were “My God, it’s dark in here!”

Supposedly, the studio was dark and Garden did not realize the microphone was on. However, the newspapers that reported on KYW’s debut in late 1921 did not mention such an occurrence, and neither did radio magazines.

They did, however, take note of the fact that she was the first opera star to speak directly to the audience by means of radio. So, while the quote may be apocryphal, it is no myth that Mary Garden was a radio pioneer, who made opera more accessible to people who might never have heard it before.

By the way, according to the New York Times, the first announcer on KYW was the station’s then-chief engineer Ernest H. Gager, who introduced Mary Garden to the radio audience.

CONTENT ISSUES

Unfortunately for KYW, broadcasting only opera soon proved impractical – there were days when no performance was scheduled, and other times when Mary Garden’s company was in another city.

Meanwhile, anecdotal evidence suggested that interest in radio had increased: when KYW’s broadcasts of opera began, there were an estimated 1,300 radio sets in greater Chicago. By the close of the 1921-1922 opera season, demand for receivers had increased so much that manufacturers could barely keep up. According to Radio Broadcast, about 20,000 sets were in operation by January 1922.

Whether or not that was an exaggerated figure, KYW still wanted to keep their audience happy, with or without opera; so, the station began hiring local talent to provide additional programming. The man who was tasked with supervising the music was Morgan L. Eastman, a well-known orchestra leader who had conducted Chicago’s Commonwealth Edison Orchestra, as well as the Edison Symphony Orchestra.

Given his access to local talent, he was the ideal person to serve as KYW’s musical director. By early 1922, Eastman and an ensemble of performers were giving regular concerts on the air. And as the station’s programming expanded, KYW also hired Wilson Wetherbee, a former journalist, to serve as the station manager; he began working at KYW in May 1922, and remained there throughout the rest of the 1920s.

WIDENING THE FORMAT

At first, KYW tried to stay with mainly classical or light opera, but gradually, the station began trying out other genres, including dance bands that played popular hit songs.

Among the most popular was Isham Jones and his Orchestra. By 1923, vaudeville star Wendell Hall was a frequent guest on the station, playing his ukulele and singing such hits as “It Ain’t Gonna Rain No Mo’” and “Underneath the Mellow Moon.” Another popular program that debuted in 1923 and continued to do well for KYW during the mid-1920s was the Midnight Review, a variety show that featured performers like the Duncan Sisters, the Coon-Sanders Original Nighthawks, and Paul Ash and his Orchestra.

And while nearly all of the performers on the station were white, occasionally KYW would broadcast a Black dance band, such as Clarence M. Jones and his Wonder Orchestra.

NEWS

In the early 1920s, when KYW was establishing its own regular programming to augment the live opera broadcasts, the station also began to report on daily news – something only a few radio stations were doing at the time.

At first, KYW affiliated with the Chicago Tribune for news bulletins, but by September of 1922, KYW was getting its news and sports scores from the Chicago Evening American; there were also commentaries and editorials from the Chicago Herald and Examiner, book reviews from the Chicago Evening Post, and business news from the Chicago Journal of Commerce. KYW also began airing market quotations and reports from the Chicago Board of Trade.

By mid-1923, the station had increased its news reports, referring to newscasts as the “World Crier,” with news bulletins on the half hour throughout the broadcast day. The experiment did not last, however, and KYW gradually cut back on World Crier newscasts; by 1926, the station was offering an in-depth newscast in the early morning and another around dinner time.

MORE LOCAL MATTERS

In addition to news and features, KYW began broadcasting some local sports, including several Major League Baseball games and college football.

It was also a time of experimentation with other kinds of programs: in March 1923, Samuel Insull, President of Commonwealth Edison, decided to broadcast a business meeting, during which he read his company’s annual report. While this may sound boring to us, the average person in 1923 had never listened to a corporate executive talking with his board of directors; the audience was fascinated by it.

KYW also broadcast local civic events, such as “National Hospital Day,” which celebrated the importance of hospitals to a community. On May 9, 1924, the Nurses’ Glee Club of Wesley Memorial Hospital entertained, and hospital superintendent Eugene S. Gilmore discussed Wesley Memorial’s role in public health.

CHILDREN’S AND RELIGIOUS TIME

There were two other areas of programming that KYW developed during those early years: children’s programs and religious programs.

In January 1923, Robert Campbell, better known as “Uncle Bob,” debuted a program where he read bedtime stories to the little ones. Just like the hosts in other cities who did the same thing, Uncle Bob’s show too became very popular with parents who could not get their kids to go to sleep without a bedtime story.

Just about a year later, in April 1924, there was a different announcer portraying Uncle Bob:Walter Wilson. But no matter who hosted it, it remained a very popular program throughout the 1920s. As for religious broadcasts, KYW offered sermons by local preachers, but in late December 1922, the station began an affiliation with the “Chicago Sunday Evening Club,” a popular—and influential—mainline Protestant organization whose members included some of the city’s best-known philanthropists and civic leaders. The Sunday Evening Club’s services were broadcast from Orchestra Hall, and featured a 100-voice choir, as well as nationally-known guest preachers.

Just like grand opera had its loyal fans, these religious broadcasts were greeted with appreciation by people seeking spiritual comfort.

EARLY MOVES

As the Department of Commerce gradually opened up the AM band, KYW was moved to 345 meters (870 kc).

Unfortunately, some of the listeners complained that they could no longer hear the station. So, in September 1923, the station was moved to 536 meters (560 kc), which the Westinghouse publication “Radio Broadcasting News” applauded: “Now, [radio fans] from coast to coast and in Honolulu will be able to get KYW.”

With more listeners hearing KYW’s programs, Westingouse wanted the station to get a better transmitter. In April 1925, the company announced that the new transmitter for KYW would be arriving from KDKA in Pittsburgh, where Westinghouse engineers were working on it. KYW was currently using 1500 Watts – one of only thirteen U.S. stations the DOC had authorized to use 1000 Watts or more.

The new transmitter, scheduled to be put into use sometime in late summer, was supposed to improve the station’s sound; in typical Westinghouse hyperbole, the press release asserted that KYW would now be like KDKA, “one of the most powerful broadcaster[s] in the world.”

NOT JUST A MOVE DOWN THE DIAL

There were more changes on the horizon for KYW in 1925.

The station was about to leave its old studios and move to a new location – and larger studios – at the Congress Hotel. In fact, in preparation for the move, engineers were putting up two 125-foot steel towers on the roof of the building. A new 20 kW transmitter was installed, the first water-cooled unit in the Midwest.

There would also be some personnel changes: veteran KYW announcer Edwin H. Borroff was promoted to manager of the new Congress Hotel studios, which officially opened in mid-October, with a star-studded evening of music featuring the Chicago Civic Opera Company, the Apollo Male Quartet, the Coon-Sanders Original Nighthawks Orchestra, and many other local entertainers.

In late 1926, the National Broadcasting Company made its debut; it would become the first national radio network, with affiliates in cities large and small. In Chicago, WGN became an affiliate of what came to be called the Red Network; a second network debuted on January 1, 1927, known as the Blue Network, and KYW was one of its stations, as were the others owned by Westinghouse.

Within the next few months, additional stations would join, including WRC in Washington DC, WBAL in Baltimore, and WJR in Detroit. This would soon prove important to the future of several of KYW’s best-known entertainers, including Morgan L. Eastman.

THE LOCAL ANGLE

As the National Broadcasting Company became more and more dominant in the programming of its affiliates, including KYW, many of the local performers were not being heard as much – unless they were on a network program.

Chicago still had a few independent stations, and performers who wanted to be heard more frequently sometimes decided it was time for a change. In the case of Eastman, he was still making a good living at KYW, in addition to teaching music and conducting the Edison Symphony Orchestra. But he had also maintained a good relationship with Samuel Insull, the owner of Commonwealth Edison.

Insull had purchased two Chicago stations, WBCN and WENR, and created the Great Lakes Radio Broadcasting Company, with an eye on purchasing several other stations. In the summer of 1927, he offered Eastman the opportunity to be his program director, and Eastman said yes.

Losing such a well-known air personality was probably not easy for KYW; not only was Eastman a widely admired conductor, but he seemed to know everyone in the music industry. Thanks to him, KYW had been able to book some of the era’s biggest entertainers. Among the biggest was vaudeville and recording star Al Jolson, who performed on the station in late April 1927, joining with other celebrities to help raise money for victims of devastating floods in the south.

ENDURING AN EXODUS

As it turned out, Eastman was not the only person who decided to leave KYW.

Radio Digest reported that most of the musicians who had performed in Eastman’s ensemble left with him, as did some of the announcers, and even the chief engineer, Ernest Gager. By the end of 1927, Eastman was being heard on Insull station WENR, conducting the Edison Symphony Orchestra.

As for KYW, there were still the popular programs on the Blue Network. But soon, the station would have several new radio stars, including a woman announcer who hosted a unique morning show. And then, it up and moved to another channel – and then over 750 miles east.

More about that in part two.

– – –

Donna L. Halper is a media historian, educator (Associate Professor of Communications and Media Studies at Lesley University), and radio consultant.

She is the author of six books and many articles about the history of broadcasting. Contact her at: dlh@donnahalper.com

– – –

Did you enjoy this article? Would you like to know when more articles like this are posted? It only takes 30 seconds to sign up here for the one-time-a-week BDR Newsletter.