Audio Sounds: A Broadcast Engineer Discovers An Audio Wonderland

[December 2010] The Audio Engineering Society (AES) is often overlooked by broadcast engineers because it does not usually focus as much on the RF side of things as some of the other conventions. Kim Sacks not only attended, but was on a panel at this year’s AES convention – and discovered a very good place for broadcasters to learn about the audio side of their craft.

This year I had the opportunity to attend the 129th Audio Engineering Society Convention, held in San Francisco California at the Moscone Center from November 4 – 7. This would be my first time attending an AES convention, so I was extremely excited, even more so than the first time I attended an NAB convention.

A Different Vibe

In a sense I was expecting the AES convention to be somewhat like the NAB convention. Boy was I wrong. I quickly discovered that the AES convention is on a completely different level than NAB.

If I had to compare the two I would say NAB is more oriented toward exhibits and new product releases, while AES leans more toward intellectual stimulation via technical papers, workshops, tutorials, and other educational sessions. This year had a larger focus on broadcast engineering than AES convention in the recent past thanks to the efforts of David Bialik.

As I review my notes, it was clear David did a wonderful job putting the Broadcast and Streaming sessions together. In this article I will give you a general overview of my experience at the AES convention.

As I review my notes, it was clear David did a wonderful job putting the Broadcast and Streaming sessions together. In this article I will give you a general overview of my experience at the AES convention.

Day 1 – Diving In

It was a short 2 block walk from our hotel to the Moscone Center North. When my husband, Bill, and I arrived at the  center we headed directly to registration.

center we headed directly to registration.

The lines were a bit thin since exhibits did not open until the next day, but Bill and I were directed to the front of the line since we were both panelists for sessions. We got our badges and ribbons and were ready to go within 15 minutes. This was easier than registration at NAB has ever been.

Once we had our badges in hand, we were ready to attend a few sessions.

Considering that Bill and I have designed several products for professional audio in broadcast facilities we decided our first stop would be a session titled Is Your Equipment Design a Noise Problem Waiting to Happen? It was presented by Bill Whitlock of Jensen Transformers.

The main point of this session was the fact that dirty power lines are well tolerated by properly designed equipment. The approach of trying to distribute pure sine wave power is not the solution; Whitlock refers to this as “Power-Line Primadonna.” The real solution is to fix the noise sensitivity problems in the equipment itself.

The main point of this session was the fact that dirty power lines are well tolerated by properly designed equipment. The approach of trying to distribute pure sine wave power is not the solution; Whitlock refers to this as “Power-Line Primadonna.” The real solution is to fix the noise sensitivity problems in the equipment itself.

Bill and Bill Whitlock are good friends, so for us this was like preaching to the choir, but you would be surprised at how much equipment does not address this issue properly. In short, there are no magic curealls for noise problems such as hums, buzzes, pops and clicks. This session and others that were hosted by Whitlock covered subjects such as safety ground (earth), AC noise, 2 prong vs. 3 prong devices, poor interface noise rejection, shields connection issues, affects of magnetic fields & electric fields, and shielding & RF interference. For more information on these subjects you might want to visit http://www.jensen-transformers.com/apps_wp.html

The next session we attended was Case Study of Punganet: Uniting Radio Stations Across a Country, presented by Kirk Harnack and, via Skype, Igor Zukina. Interestingly, this was an AES first, with the copresenter of this session making his appearance remotely via Skype.

This session explained the IP-based content distribution network used by Iwi Radio of New Zealand. This distribution network appears to be extremely versatile compared to traditional distribution systems, allow-ing high quality, real-time content sharing across a nationwide network of 23 radio stations with an easy-to-use web-based interface. One advantage, among many, of this system is the ability to share individual studio sources, such as an individual microphone, across the entire network.

This session explained the IP-based content distribution network used by Iwi Radio of New Zealand. This distribution network appears to be extremely versatile compared to traditional distribution systems, allow-ing high quality, real-time content sharing across a nationwide network of 23 radio stations with an easy-to-use web-based interface. One advantage, among many, of this system is the ability to share individual studio sources, such as an individual microphone, across the entire network.

After Kirk’s session we roamed the hallways a bit to socialize, bumping into old friends and making new ones. The show was starting to wind down for the day when Bill and I joined up with Robert Orban and Greg Ogonowski. We all had so much to talk about and had a wonderful time at a San Francisco dinner discussing the events of the day.

One day down, only three more days to go.

A Day Packed With Audio

We started the second day with An Overview of Audio System Grounding and Interfacing, presented by Bill Whitlock. This session dealt with more hum, buzz, noise and interference problems – this time on a systems level, covering the basic do’s and don’ts of eliminating these issues.

The next session I attended was Innovations in Digital Radio, Chaired by David Bialik with panelists, Steve Fluker, Frank Foti, David Layer, Skip Pizzi, Tom Ray, Geir Skaaden, and David Wilson. This session was a general overview of the progression of HD radio in the past few years, primarily focusing on how the new power increase has affected coverage areas compared to the analog signals. David Bialik also discussed the lack of public education about HD radio.

The following two sessions were a good part of the reasons why I made it to this AES convention.

The first session, Listener Fatigue and Retention, was chaired by David Wilson of CEA. The panelists included Sam Berkow, Marvin Ceasar, Frank Foti, JJ Johnston, Sean Olive, Thomas Sporer, and last, but not least, Bill Sacks.

I would have to say that this session had more of a taste of traditional AES sessions than I was expecting. However, and you can trust me, it was not as fatiguing as it might sound.

I would have to say that this session had more of a taste of traditional AES sessions than I was expecting. However, and you can trust me, it was not as fatiguing as it might sound.

The first three panelists primarily discussed mechanical cochlear (ear hairs) fatigue, central nervous system fatigue, and how these hair cells depolarize due to high loudness leading to mechanical and biochemical fatigue. Since no standard methodology exists to measure listening fatigue, in a sense much of that discussion is theoretical.

Can They Tell? Do They Really Care?

Sean Olive did have a presentation that I found to be extremely enlightening. It addressed the question of “do younger listeners even hear a difference?” His presentation included results of double blind comparative listening tests conducted on high school students ranging in age from 15 to 18. These tests included comparative listening of MP3’s vs. linear PCM WAV.

Olive’s study was able to prove that younger ears can hear the difference between uncompressed audio and MP3 – and they strongly preferred linear uncompressed audio.

The last two panelists of this session were more oriented toward the broadcaster’s and musician’s side of things. Frank Foti explained how listeners fatigue can be caused in a broadcasting environment and how processing can produce fatiguing artifacts. He also provided a very demonstrative set of audio samples.

The last panelist was Bill Sacks, who had yet another perspective of listener fatigue and retention. Bill decided to get feedback from musicians, who have a completely different perspective on how music is heard and retained. This was followed by an interesting set of questions and answers between those in the recording industry and those in radio, a bridge that I think should be crossed more frequently.

Streaming Audio Explained

The next session was Audio Processing for Streaming: Finding the Silver Lining in the Internet Cloud, Chaired by Bill Sacks www.optimod.fm.

The panelists included Ray Archie, Skip Pizzi, Frank Foti, and Greg Ogonowski. This session explained Internet radio and streaming audio with details of the feeble beginnings of streaming media content and how it has grown to what we have today.

Ray Archie discussed how streaming facilities work, how to manage them, and a glimpse at how meta data works. Frank Foti then explained how bit-rate affects performance and intelligibility of coded audio. Foti described why pre-emphasis based processing should not be used for streaming and how multi-band processing should be applied to coded audio.

The last panelist was Greg Ogonowski. He began by stating he was an early proponent of HE-AAC, originally developed primarily for mobile devices, and why it is more efficient and more musical than MP3 or WMA for coded audio. He also spoke about the divide between digital audio folks and the IT community.

According to Ogonowski, the four main ingredients for quality audio streaming are a good clean source material (preferably linear PCM), professional sound cards, good audio codec, and profession audio processing. He then went on to explain the advantages of using a professional sound card like the OptimodPC 1101 – with its built-in, on-board DSP to process the audio – for use in streaming as compared to the output from $29 consumer sound cards.

Ogonowski also explained why audio processing is necessary for streaming content, but why FM processsors are not appropriate for coded audio. Finally Greg taught us how different player apps decode HE-AAC.

All of this material was followed by another question and answer segment.

Processing Wizards Share

November 6 th began with Audio Processing for Radio, chaired by Tom Ray of Buckley Broadcasting. The panelists included Steve Fluker, Frank Foti, Jeff Keith, and Robert Orban. Ray introduced this session by stating the main subject being covered – why radio stations process audio they way they do.

Steve Fluker discussed why radio sounds the way it does. Then he pointed to a question that he recently received from an audio engineer: “Why can’t we put the audio processor in the receiver and let the end user decide how much processing they want?” Fluker explained that covering up the noise on the carrier is the problem. Another factor would be the difficulty the average listener would have in understanding how to actually set up the processing.

Another point Steve made was the fact that digital radio stations cannot over-modulate. Frank Foti then opened the door to an explanation of pre-emphasis processing by turning it over to Robert Orban, crediting Orban with creating the FM sound we all know today.

Orban began his presentation explaining why radio stations need to control dynamic range and inconsistent levels, and how radio stations create their branding with a signature sound. He then spoke about the differences of processing audio for Internet radio, AM, FM and HD radio, and the variety of types of listeners radio stations target, including how women listen to radio differently than men.

Listening to One’s Own Station

Orban further explored the difference between harmonic distortion and intermodulation distortion. He said he believes radio station people should try listening to their station through cheap ear buds to better hear the effect of crunchy distorted low end through them.

Another subject Orban covered was listening environments and how to properly balance the sound of a radio station based on the target audience and what types of radios those targets use to listen.

Then Foti began his part of the presentation by explaining how the loudness wars began, with listeners using analog tuners with AFCs that were being sucked into loud radio stations that had the in-your-face sound. Although he understands the psychological effects of “louder is better” in the minds of program directors, he described signal processing in the industry as extreme.

Feeding the Listeners Consistent Sound

The floor was then turned over to Jeff Keith who spoke about how radio has to create a consistent sound for different types of content without the listener having to continuously adjust their radio.

Keith explained how over-processed audio from mastering studios can – and does – conflict with the audio processing used in radio.

The discussion included a brief history of audio processing for radio – how audio processing had been done in the past, including air chains using several audio processors plugged together to obtain a station’s “signature sound.” Several called it was a fun time for experimentation and innovation – some of the best known processors came out of this time period, but the Modulation Wars led to problems in the long run.

Wrapping up this part of the discussion the panelists agreed that the new digital products provide better quality control for both the manufacturers of audio processors and radio stations.

A Proposal

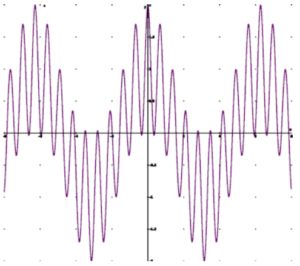

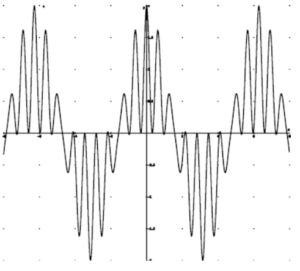

Frank Foti’s proposal of a new method of subcarrier modulation for FM multiplex utilizing a single sideband suppressed carrier (SSBSC) led into a back and forth discussion between Foti and Orban.

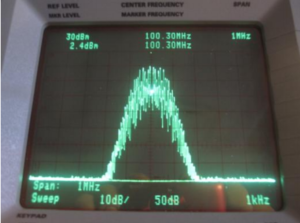

Foti first gave a brief background of how our current FM multiplexed signals work. He recommended investigating using a composite signal utilizing only the lower 38 kHz side band and a suppressed carrier. A Stereo Generator with SSBSC: MPX bandwidth would be reduced from 53 kHz to 38 kHz. The L-R would be carried within the SSB spectra of 23 kHz to 38 kHz.

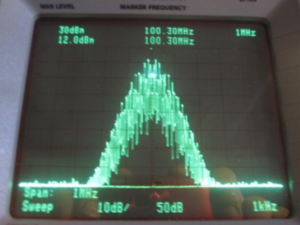

Double Sideband

Single Sideband

Foti suggested that reduction in multipath results from reducing FM sideband pairs, thus increasing the modulation index. Reduction of occupied bandwidth in the L-R sub-channel increases the modulation index by a factor of two, resulting in a direct reduction of multipath. Additionally there is the potential to have 4 dB SNR improvement in stereo.

A Better FM Signal?

This method would reduce overall FM transmission bandwidth and improve stereo performance within finite bandwidth passband filters, cavities, multiplexing systems, and antennas. This would especially benefit international broadcasters using 100 kHz channel spacing. SSBSC:MPX would be compatible with existing modulation monitors, and current (post 1973) receivers. And less harmonic content would be generated when composite clipping is deployed in the audio processor.

Another benefit would be significant protection for RDS, SCA, and HD-Radio. SSBSC would offer increased protection to conventional analog signal, should HD Radio increase power. In order to keep proper decoding levels, the lower sideband is modulated with a 6 dB increase in order to maintain the ratio for proper stereo separation.

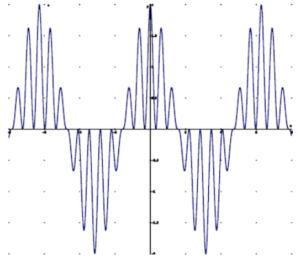

FM deviation: 1 kHz Left Channel Only Double Sideband DSBSC FM deviation: 1 kHz Left Channel Single Sideband

Foti thinks this method – with fewer sideband pairs – would reduce the perception of multipath. He released a formal White Paper about this proposal at this past NAB and also to the FCC. This method suggests that receivers only see a 38 kHz bandwidth rather than 53 kHz bandwidth. It should also be cross compatible without problems with existing equipment. Foti also feels this method may also help reduce potential annoyance in analog signals caused by HD channels.

Foti concluded by playing an audio clip showing that separation is maintained with his proposal.

Another Idea for FM

Bob Orban had a few thoughts regarding Foti’s proposal. He noted that using only the lower sideband of the stereophonic subcarrier has a long history. In fact, two of the original systems presented to the FCC during the FM stereo proceedings in the 1960’s were SSB systems.

For example, in the early 1980s, Bob Tarsio (Broadcast Devices) investigated this system and did some informal field tests. The results showed the SSB system caused more audible multipath distortion than the current DSB system. However, Tarsio’s SSB generator was analog and not phase-linear, so the increase in audible distortion might have been created in the receiver, not by the difference between SSB and DSB operation.

Maintaining the correct peak level control of the composite signal requires the frequency response to extend well below 20 Hz. To maintain that peak level control, SSB cannot introduce phase distortion. This is easy to do with DSP by the phasing method (using Hilbert transform filter in DSP) or the Weaver method (using a complex-domain lowpass filter).

In SSB generation, the coding delay and the filter length increases as the low frequency cutoff is decreased. SSB cannot have response to DC because this would require filters with infinite delay and infinite length.

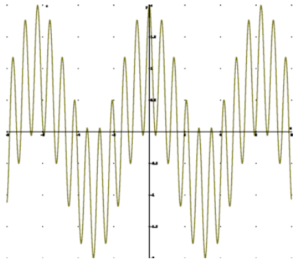

Orban offered a different solution for consideration: vestigial sideband operation (VSB).

Vestigal Sideband Operation

VSB operation means that the stereophonic subcarrier is SSB from 18 kHz to Fc – the crossover frequency between SSB and VSB operation. In the frequency range below Fc, the sum of the magnitudes of the upper and lower sidebands is unity and they are time-aligned (i.e., no phase distortion).

Left only modulation.

VSB allows response to DC and prevents overshoot in the composite waveform. VSB is a completely linear process where superposition and scaling hold. As a system well-known in the art, VSB is nonproprietary and free from intellectual property constraints.

Summing up the discussion about SSB vs. VSB Foti agreed there may be better methods of achieving the desired results, and this sort of dialogue this opens the door to better the industry. He invited others to join in the process of development and testing.

After this intense session it was time for a break and some food. Plus, I had to prepare for the session on which I was to be a panelist. At this point I was beginning to get a little nervous.

An Opportunity to Speak

This was the main reason I made it out to this convention: Careers in Broadcasting, chaired by Chriss Scherer and attended mostly by students interested in pursuing a career in broadcasting. The panelists included William Blum, Russell Brown, Steve Lampen, and myself.

The panelists covered subjects such as what publications to follow, how to find a mentor, what students need to know to be a broadcast engineer, and how to become certified through the SBE.

Wrapping It All Up With a Walk Around

After three action-packed days full of sessions I decided to take some time and walk around the exhibit floor. This was much like walking the radio hall at NAB – except it was saturated with tubes (pun intended) and analog gear.

Scope trace of the baseband output of VSB 40% USB/ 60% LSB. Left only modulation. Scope trace of the baseband output of VSB 10% USB/ 90% LSB. Left only modulation.

First Bill and I headed over to meet with a friend from the UK at the APRS booth. Then, we went over to the NTI booth to check out new measurement instruments.

Our next stop was at the ATI booth to check out their new digital audio DA. Right across from that was the Women’s Audio Mission booth, a non-profit organization dedicated to the advancement of women in music production and the recording arts.

Before long, the Audio Science booth caught my eye so I went over to check out the ASI5211.

This is an improved version of their last sound card, now with 24-bit A/D and D/A converters.

This is an improved version of their last sound card, now with 24-bit A/D and D/A converters.

Of course what would an audio convention be without the opportunity to play with a few microphones. I got a chance to try an AEA ribbon microphone or two; oh, do they sound lovely! Then I had to run over and try out the Telefunken microphones.

Then the nearby Manley Labs booth drew me over with their cool “Tubes Rule” T-shirts.

One thing I really wanted to do was get my hearing tested at the show, unfortunately the environment just was so loud, even inside of the “sound proof” trailer, that I do not trust the results.

just was so loud, even inside of the “sound proof” trailer, that I do not trust the results.

Last but not least I stopped by the Bourns booth – after all how could I leave San Francisco without some good pot samples?

FYI: Recordings of these AES sessions and more are available for purchase by going to their website at http://www.aes.org/events/129/ and clicking on Audio Recordings on the right hand menu list.

– – –

Kim Sacks is a broadcast engineer in Washington, DC. You can contact her at radioctrldwife@gmail.com or via her website at www.optimod.fm

– – –

Did you enjoy this article? If so, you are invited to sign up for the one-time-a-week.BDR Newsletter.

It takes only 30 seconds by clicking here.

– – –