Calling the Engineer Over the Years: Almost Anything Besides Smoke Signals

[November 2016] It is time for Clay again – this time remembering the Good Ole Days before evolution changed the way station engineers got called.

Recently, I had been doing some reflecting (it comes with the territory at this age) about how the broadcast station reached me before the advent of cell phones.

I thought I would dig back into my dimming memory of over 50 years in the radio business to review the various methods the company/station where I worked had for reaching me when they had a technical snafu – something they felt only I could resolve.

I believe that you will agree, we have come a long way.

When a Tech Was Always There

At one time, actually not so long before I started, stations were required to have a live-operator, the holder of a First Class Radiotelephone from the FCC on duty at all times.

Theoretically, he was the one that looked after a station’s technical needs.

Interestingly, the larger stations usually had a whole staff of – maybe 60 or more – engineers. On the other hand, small stations occasionally found themselves without engineers during the some war years, and had to seek waivers just to stay on the air.

True, fifty years ago we did not have these finicky computers but we did have a plant full of vacuum tubes and other parts that could – and did – fail during the broadcast day. There are still some transmitter sites around the country where you can visit and see the machine shops where the engineering staff worked to keep the station on the air.

Where Did They Go?

As most folks know, over the years, changes in the industry’s transmitters and engineers have led us to a point where there is no longer a large staff of engineers, but rather just one engineer who services many stations.

That is why, today, it is often likely there is no technical person around when trouble hits. Of course we now have way to remote control things in a way that would have been viewed as science fiction back then.

Frankly, the number of times a radio station back then needed to reach an engineer was not that much different than it is now. The big change is that things now are incredibly more complex. So complex, in fact, some equipment is even able to call for help all by itself!

When You Needed Someone

In 1961 we did not have cell-phones, pagers, nor any other means of instantly reaching a person. Basically, the station hoped you were sitting around waiting for their call. In addition to a land-line phone, it meant you:

- Left other phone numbers where you might be reached.

- Knew where all the pay-phones were located.

- Always had a pocket full of change (for the phones).

- You listened to the station you were working for just about all the time.

Clearly finding the engineer was not always easy. A station might end up calling around, to see if anyone you knew happened to know where you were. (Some sharp GMs seemed to just know exactly how to find you!)

Two-Way Radio Comes to the Car

An improvement came as technology provided a two-way radio to be mounted in your car.

First used by police in 1930, eventually the technology filtered down to commercial users.

To make it work, the transmitter was mounted in the trunk (it originally took up the whole rear seat), and was wired to a head-end in the passenger compartment. It was what was called a simplex system: You pressed the button and spoke, then released it to hear the other person.

An alternative to make contact a bit easier was using a ham radio, but that only worked if someone at the station was also a ham – or the station could find someone to relay the message.

Essentially, finding the engineer was the still the hardest part of getting help.

They Want Us to Call Them Now!

Radios began to get smaller as inventions made technology smaller, especially after transistors appeared in the late 1940s.

The next great invention that was immediately adopted was the pager, or as they were known back then – “The beeper” (The phone company called them “Bellboys”).

These little gizmos were a simple VHF or UHF receiver with a decoder and sounder. When you called the number associated with the device – it beeped. That was your signal to call a prearranged number. If the person you “beeped” did not call back right away – you called the number again. Sadly these little critters did not have any indicator that it had been called (that came later).

These little gizmos were a simple VHF or UHF receiver with a decoder and sounder. When you called the number associated with the device – it beeped. That was your signal to call a prearranged number. If the person you “beeped” did not call back right away – you called the number again. Sadly these little critters did not have any indicator that it had been called (that came later).

The next advancement in ‘leash technology’ I had was the “Tone and Voice Pager.” These were a bit bigger and contained a very small speaker.

When the pager beeped, you would immediately pull it off your belt, or out of your shirt pocket, and place it next to your ear to (hopefully) hear the message. These were cool because they could deliver a selective message: “Call the station,” “call home,” etc. – At least it worked if the caller told you which station to call!

When the pager beeped, you would immediately pull it off your belt, or out of your shirt pocket, and place it next to your ear to (hopefully) hear the message. These were cool because they could deliver a selective message: “Call the station,” “call home,” etc. – At least it worked if the caller told you which station to call!

Interestingly, carrying those pagers all the time quickly taught us where the signal did not penetrate: some parking garages or malls, for example. At least we could tell the boss “where” we were when he called – and we failed to answer.

I recall putting this system to work rather quickly as a means of controlling ham-radio systems. A receiver tuned to the paging system’s frequency, a DTMF decoder and you were set. You could call yourself from the then new Touch Tone Phones and enter digits that would make things happen. Pretty neat! I also recall adding DTMF encoders (known as touch tone pads) to telephones for this purpose.

A Better Pager

Then came along the Digital Pager.

With these things, the caller would enter the number they wanted you to call back.

There were a number of advantages to these devices. Foremost: they would save more than one number, so you could call back when you got to a phone.

There were a number of advantages to these devices. Foremost: they would save more than one number, so you could call back when you got to a phone.

Of course, all of these systems relied on your ability to locate a pay phone to make that return call in a timely manner. Remember mobile telephones had not come along yet. You got pretty good at knowing where pay-phones were located. On the other hand, you had to remember tp carry change as each call required cash.

The digital pagers also had a better footprint, so located those “quiet zones” where you could not be reached was a bit harder.

The First Mobile Phones

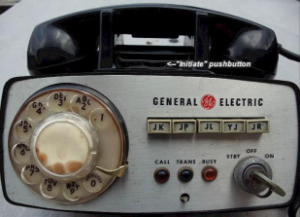

By the 1960s, the telephone company and some private carriers had mobile telephones.

These were basically two-way radios with a trunk-mounted transceiver and a control head up front. It had either a “call” button or, later, a rotary dial.

At first, a throwback to the 50’s, you would call out to the operator and they would connect you. It was, yes, sort of a party line, as anyone with a radio could listen.

Later phones allowed some direct dialing. They worked pretty well and would allow you to make and receive phone calls over an area limited by the coverage of the system (forget going out of town and having it work). But you had to be in the car to use it, smaller two-way gear was still to come.

The world did not have to wait long, though.

Early Handheld Units

In the 70’s I found myself working for a company that did paging and radiotelephones.

Here I had a digital pager on one hip and a Motorola MT500 on the other. Of course they were not little two-way radios you could slip in your shirt pocket today

The MT500 was fairly big (about the size of eight i-Phones stacked together), and looked very much like the kind of radio worn by police (I was viewed by some in a unique way back then).

The MT500 was fairly big (about the size of eight i-Phones stacked together), and looked very much like the kind of radio worn by police (I was viewed by some in a unique way back then).

It had several frequencies and was controlled by an external mobile telephone terminal. This enabled the device to have its own unique phone num-ber. It was half-duplex, i.e., you had to push the transmit button to talk and you heard the caller on a loud-speaker.

I recall being in a grocery store one time when the wife called to remind me to pick up something. A lady standing nearby was dazzled and wanted one. This system was clunky, but it was functional and I could be reached by anyone by phone and I could make phone calls. The biggest customers for this technology were doctors that were on call.

Private Paging

Paging was a viable business back then with the telephone company and private common carriers as well as a number of re-sellers serving a number of customers.

To extend the coverage area of paging systems, simulcast systems were installed with transmitters scattered throughout the area. These systems were the forerunner of SFN’s (Single Frequency Networks) that are talked about today in broadcasting.

Along the way some experiments were conducted using FM broadcast station sub-carriers for private paging. Motorola even made an SCA Pager in limited quantities. One local station I know of even did some experimental work with these during a convention of common carriers that was held in Seattle. Coverage was not as good as hoped.

Early Cellular

About that time, cellular was being planned in earnest.

I was lucky as the company I was working with was not only involved in paging and radio-telephones, they were also an early partner with the McCaw’s and I got to see how this system was going to be really cool.

An interesting side-bar, the technology of site selection for these first cell sites was aided by a, then brand new technology that employed a terrain data base to evaluate potential sites without having to go out and “drive them” or use manually generated profiles using USGS Maps.

At first, the transmission and audio were analog.

Early cellular phones were all mounted in vehicles, much like land-mobile two-way radios. You took your vehicle to a shop where they installed the antenna (many on the rear window), a gizmo in the trunk and a control head that had a handset. There was still the limitation of being reached when you were not in a vehicle with one of these

So, I still carried a pager.

Portable!

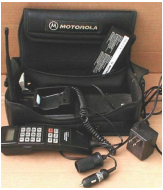

Then came the first truly portable phones, suitably in a bag.

Phones like the Motorola Associate were carried in a bag you would hook on your shoulder. They were not light, but they were nice and you could take them almost anywhere you needed to be.

Phones like the Motorola Associate were carried in a bag you would hook on your shoulder. They were not light, but they were nice and you could take them almost anywhere you needed to be.

Hand Held Cell Phones

Finally, in the mid-80s, we get to the much hyped, hand-held cell phones hitting the market, Smart they were not – at least in terms of what you can do with an iPhone today, but the main thing is they were truly portable – as long as you did not hold them up for long.

Yes, I was one of the early ones that carried a “brick.” That was about the size of it – and let us not forget the rubberized antenna that stuck out the top.

Yes, I was one of the early ones that carried a “brick.” That was about the size of it – and let us not forget the rubberized antenna that stuck out the top.

Battery life was sort of so-so, and airtime was well north of $1.00 per minute! But the main point is that you could be reached in a lot of places for a private phone call.

When cellular was launched the days of pagers were numbered. Soon, they joined the rotary phone in the great dust heap of history, along with IMTS mobile phones and, to a great extent, land-mobile two-way radios.

Now It Is Really in Your Pocket

We have come a long way.

Now we have what are called smart-phones that we put in our pocket and have become addicted to the chain that previously only our employers told us we must have.

Who would have thought that we would be carrying a device that would not just be a telephone but a communicator that would enable us to access a world of things – including determining what was wrong with the broadcast plant after its computer called you to report an ailment?

One parting thought: did you ever notice most men now “wear” their cell phone. If you wish to reach a fellow (male) engineer – you can call them and they answer right away.

At any rate, recently I had the occasion to wonder why a particular person I was dealing with did not rapidly answer when I called her cell phone. Then it dawned on me. Most women do not wear their phone. Duh! Then again that leather belt that we use as a “holder” for electronic devices is, perhaps, a male thing.

– – –

Clay Freinwald, a frequent contributor to The BDR, is a veteran Seattle market engineer who continues to serve clients from standalone stations to multi-station sites.

You can contact Clay at K7CR@blarg.net