Exercise and Expertise: How Early Broadcasting Promoted Health Education

[August 2013] The title “First” sparks lively debates in many areas of life. Sometimes they are driven by bets; sometimes by lawyers seeking money; and sometimes by historians who are just trying to “get the story right.” The results can be interesting – and surprising.

Doing Internet research can be fun, but it can also be frustrating.

It is fun to find some new piece of information that was previously available only in old books or on reels of microfilm. But it is frustrating when a fact is erroneous – and yet it gets repeated endlessly on website after website.

I do research for a living and I find that even the most reputable sites may occasionally contain an error.

When I see one that falls within my area of expertise, I like to get in touch and offer to correct it. That is what happened in this case; it led to my writing this article about health, exercise, and early broadcasting.

Trying to Get it Right

I must admit my interest in health and exercise programs on the radio was quite unexpected.

It all started when I was researching something entirely different: the history of an early commercial radio station, KYW, which went on the air in 1921. While doing my research, I was surprised to find several websites assert: “In 1924, the radio station KYW in Chicago became the first in the United States, and most likely in North America, to broadcast a health education program of daily morning exercises. This radio program was done in collaboration with the physical education staff of the Chicago YMCA.”

Now, let us not take anything away from the impressive track record of the YMCA nor its Jewish counterpart, the YMHA. Both organizations were early proponents of broadcasting and both offered classes in amateur radio. Nor do we want to take anything away from KYW, then owned by Westinghouse and located in Chicago, IL.

Indeed, KYW was among the first stations with a regular newscast and broadcasts of live opera.

The website that started this research

But the first in the United States to broadcast exercise by radio? Not exactly. In fact, not even close. As we shall soon discover, the first such broadcasts were actually in 1922, definitely in Boston, and possibly in Pittsburgh and Detroit.

Just a Slight Detour

And here is where the story took an amusing turn.

As a media historian (author of five books and many articles), I knew that I had read something somewhere about exercise by radio as early as 1922. So I searched for the exact date of that early show and some information about the person who hosted it. All I had planned to do was send a simple correction and then return to my research on KYW.

But as it turned out, the correction was not so simple. In fact, the more research I did on the topic, the more it seemed that exercise by radio deserved a closer look. So I decided to write about it. But I never expected my research to uncover a story that was about far more than the need for physical fitness.

Using radio to teach about health was a story of good intentions, as well-respected doctors and social workers went on the air to encourage people to take better care of themselves and their children. Nevertheless, it soon evolved into a story about conflicting claims from “experts” regarding the curative powers of exercise; it even involved a professor who hosted a famous quiz show – except he was not really an expert nor was he really a professor.

When Radio Was New

We begin our story in early 1922, when the United States was caught up in the radio craze.

The first commercial stations – 8MK (later WWJ) in Detroit, 8ZZ (later KDKA) in Pittsburgh, and 1XE (later WGI) in Medford Hillside MA, just outside of Boston, began doing regular programming during mid to late 1920. Then, in the spring of 1922, there was an explosion of new stations, and soon there were several hundreds of stations.

Up in Montréal, Canada, XWA was the first commercial broadcast station. XWA (later re-named CFCF – “Canada’s First”) went on the air as an experimental station in 1919; by late 1920/early 1921, it was doing regular broadcasts. Toronto got its first station when the Toronto Star began experimental broadcasts in late March and early April 1922.

These broadcasts all received positive public reaction. Listeners were amazed and delighted by this new mass medium. With so many people expressing an interest, newspapers fed the public’s need for more information; the new stations and their activities quickly became front page news in many places.

A Real Part of Their Lives

It can be difficult for the average person today to understand how important radio was in the 1920s.

Today, we live in an Internet-dominated world, and most of us have easy access to information, whether from online sources, 24-hour news stations on radio and TV, or from libraries and bookstores. Adding to our “information society”

is the fact that many young people attend either a two-year or four-year university, since it is a truism that without a degree, it is difficult to get a good job.

On the other hand, in the decade from 1910 to 1920, before radio came along, information was more difficult to find. For one thing, news was mainly obtained from books, magazines, and newspapers, presenting a challenge for those who were illiterate, or blind, or not native English-speakers.

There were other ways to find out what the newsmakers were doing, but none of the options was easy. If you lived in a city with a movie theater, you could watch a newsreel, but this too required the ability to read; movies were still silent, and the explanations of what you saw in a given scene were printed on the screen, much like subtitles for a foreign film are today.

Another option was attending a speech by a newsmaker, assuming you could get to where the speech was. In urban areas it was not so difficult, since celebrities and politicians often came to town; but for people who lived far from a major population center, the one time that the big names usually came to town usually was to speak at the county fair.

One other factor limited the amount of information the average person had: because fewer people attended a university, the general public seldom had access to the best academic research and the experts who produced it. Occasionally, a famous professor wrote an essay for a mass-appeal magazine; however, there was no equivalent of today’s “pundits,” readily available to discuss any subject at a moment’s notice and validate or contradict magazine article.

Radio Really Mattered

But from the moment the radio craze took hold it brought about a number of important changes in society. For one, radio was the first mass medium to transport people to an event in real time.

No matter how many editions of the newspaper were produced, no matter how quickly the newsboys (and occasional newsgirls) got them into the hands of the public, there was a delay between when the story was reported and when people could read about it. But with radio, people could hear a church service as it was happening, or listen to the World Series inning by inning, as if they were at the ballpark, or even hear the president give a speech.

Radio also helped to equalize the social classes, expanding access to the best performers and the biggest newsmakers. In the early 1920s, much of America was racially and socially segregated, and people of color, as well as the poor, were often excluded from attending concerts.

Thanks to radio, the most famous entertainers could be enjoyed by anyone, not just by those who were upper-class and white.

In 1925 Graham McNamee was voted

The World’s Most Popular Announcer

This was especially beneficial for people who lived in rural areas: the great opera stars and stage actors came to a number of large cities, but the average farmer could seldom afford to purchase a ticket, dress up and travel a long distance to attend the show.

Radio removed those impediments: people who had a radio could now enjoy concerts and sporting events, no matter how far away from a big city they might live. And this did not only apply to entertainment; radio offered educational talk that anyone of any color, religion, or social class could listen and learn from. Although radio became known mainly for its ability to entertain, it would quickly prove that it could also educate.

Radio removed those impediments: people who had a radio could now enjoy concerts and sporting events, no matter how far away from a big city they might live. And this did not only apply to entertainment; radio offered educational talk that anyone of any color, religion, or social class could listen and learn from. Although radio became known mainly for its ability to entertain, it would quickly prove that it could also educate.

A 1924 ad in the Rockford (IL)

Daily Register-Gazette mentions

Early riser exercise programs.

Block Programming

During the early years of broadcasting, there were no individual formats as we know them today, such as all-news or all-sports, or all-hit music.

Stations did what came to be known as “block programming,” offering fifteen minute blocks of time, and each segment was different. Audio-tape had not been invented, so all the programs were all done live, and the listener had no idea whether any given evening’s broadcasts would be amazing or boring. (Actually, most listeners were so excited to hear a station in their headphones that they tended to forgive the programs that were not very good, or they dialed around until they found something better.)

Most stations focused on musical performances (maybe big band jazz, maybe opera), but there were also news headlines, inspirational messages from local clergy, bedtime stories for children, local authors or poets reading from their latest works, sports scores (some stations even broadcast live from major sporting events), perhaps a one-act play.

Health Education by Radio

The radio craze even reached into the hospitals, many of which installed receiving sets so patients could hear the programs. Advertisements for receivers even mentioned the health programs. (see ad above.)

Physicians were pleasantly surprised to discover that radio had a therapeutic effect – it seemed to cheer the patients up by taking their mind off of their health problems.

Another group that found radio therapeutic was residents of rural areas, especially stay at home wives and mothers. Radio turned out to be an excellent cure for loneliness, and helped them stay up to date with what was happening in the big cities.

Given radio’s ability to simultaneously reach large audiences in many cities, it is not surprising that members of the medical and public health communities were soon drawn to the new medium. In fact, by the spring of 1922, a large number of radio stations were broadcasting health talks.

Health care professionals back then had the same problem as they do today – there were numerous myths and legends that the average person heard, and it was crucial for accurate information to be disseminated. Radio provided an opportunity for credible and respected doctors, nurses, social workers, and dietitians to debunk the myths and misconceptions and give listeners the facts.

US Public Health Service

In the United States, one of the first agencies to use broadcasting to send out health-related information was the U.S. Public Health Service. Using station NOF, which was operated by the Navy, the service sent its first message at 9 PM on December 24th, 1921. The Health Service promised to give factual and practical advice about how to be healthier.

By our modern standards that was not especially earth-shattering but listeners learned the Public Health Service was available to them and would broadcast reliable information every week. In that first health program, the announcer talked about the need for all Americans to take care of their health and reminded listeners that many illnesses were preventable.

Health Talks Proliferate

By mid-1922, more and more health talks were on the air.

While some station owners were undoubtedly altruistic in providing time for these programs, another reason was that health talks were easy and inexpensive to produce. They did not require an orchestra or an accompanist; all that was needed was a microphone, an engineer, and someone willing to give the talk – often as volunteer (unpaid) talent.

Interestingly, long after performers began getting paid, healthcare professionals, along with educators, and members of the clergy, remained eager to participate in broadcasting, whether or not they were paid. Sometimes, their eagerness was because they genuinely believed they were performing an important service to the public. In other cases, they already received a salary from their full-time job, so they simply added a weekly radio talk into their job description.

Meeting Urgent Needs

The first radio health talks addressed the public’s concern about certain diseases.

For example, in April 1922 several U.S. radio stations had talks about prevention of tuberculosis. WGY in Schenectady NY featured Dr. Hermann Biggs, the New York State Health Commissioner, and former Chief Medical Officer for New York City. Station WJZ, then in Newark NJ, offered a similar talk by Dr. Moses J. Fine, of the Newark Department of Health.

In Massachusetts, station WBZ carried talks by Dr. Harold E. Miner, of Massachusetts Department of Public Health; in mid-July 1922 he discussed another issue that was worrying the public – the prevention of diphtheria. And both WBZ and WBAP in Fort Worth TX had regular talks from members of the Red Cross, about practical subjects like preventing accidents in the home, or knowing what kinds of foods are healthy for kids.

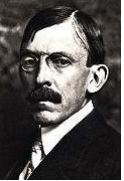

Dr. Hermann Biggs in particular soon became a radio health expert, which was good for the listeners, since he had expertise in bacteriology and infectious diseases – and he knew how to explain difficult concepts in a listener-friendly manner.

Dr. Biggs had served as New York State Health Commissioner since 1914; long before that he had been widely praised for his achievements in public health. His policies reduced the number of cases of tuberculosis and diphtheria.

Dr. Hermann Biggs

Radio greatly expanded his ability to reach the general public, carrying his messages far beyond New York. On the air, he did what he had done in print for years: encouraging people to be proactive about their health, stressing such things as the importance of regular check-ups and telling them how to eat healthier foods.

Each Friday night on station WGY and others, Dr. Biggs discussed a wide range of topics, including how to relieve the symptoms of hay fever and seasonal allergies, coping with hot weather, treating measles, and knowing which plants are poisonous. His remarks were even covered by major newspapers like the New York Times and Christian Science Monitor.

Local Connections

Throughout the early 1920s, from Boston to Dallas to Los Angeles – and even across the border in Canada – health talks became a regular feature on most radio stations. In addition to the state commissioners of health and members of the Red Cross, listeners heard personnel from local hospitals (both doctors and nurses), and representatives from the National Tuberculosis Society, the YMCA, and other agencies.

Just as today, the most popular topic was the relationship between diet and health, and there were many requests for advice about how to lose weight. 1922 was also the year when a growing number of universities decided to make professors available to give radio lectures. Some of them discussed careers in medicine (including dentistry and nursing); others talked about psychology or the latest research on infectious diseases.

Tufts College, located near Boston MA, was one of the first to offer entire courses by radio, via station WGI in Medford Hillside, as early as April 1922. The courses lasted thirteen weeks, and each week’s lecture was about thirty minutes long. Among the subjects was a course on physical fitness and athletics.

Around the same time, the University of Michigan also began offering courses, using Detroit’s station WWJ, including at least one focused on public health.

Good Information – And Bad

By 1923, the US Surgeon General, Hugh S. Cumming, was broadcasting the government’s health talks over station NOF.

But while many credible men and women with solid credentials were now on the air, radio also had a dark side.

At a time when fact-checking was rarely done and people were far less skeptical, radio provided a forum where charlatans with questionable credentials could pass themselves off as experts, even if they were not. Some stations broadcast talks by astrologers, fortune tellers, mediums who claimed they could talk to the dead, faith healers, and more.

There also was one especially notorious fraud among them: “Doctor” John R. Brinkley.

It was Binkley who claimed he could restore male virility by surgically implanting goat glands into his patients.

John R. Brinkley

For more information about Brinkley and his radio career, see my article on his life: John R. Brinkley, Early Radio’s Most Famous Fake.

Radio Meets the “Daily Dozen”

And that leads us to the story of how setting-up exercises came to radio – and then on to the mysterious life of the man known as “Professor Quiz.”

The exercise fad of the 1920s probably started with Walter Camp, a legendary college athlete at Yale who distinguished himself in four sports before going on to an equally successful career as Yale’s football coach. Camp became known as the Father of American Football, since his innovations helped to shape the way the modern game was played.

Camp became equally successful as an author, writing a number of books and contributing articles about athletics and fitness to newspapers and magazines.

During the First World War he was consulting for the military and devised a program to keep the troops more fit. His system came to be known as the “Daily Dozen,” a series of twelve exercises that could be done each day in as little as ten minutes.

Springfield MA Sunday Republican

June 1, 1924

One of Camp’s best-selling books explained this exercise regimen, and it did not take long for celebrities to begin extolling how easy it was to follow his system, and how it helped them to feel healthier. Even the record companies got involved: Victor Records offered a portable phonograph with a set of songs designed for doing exercises. The ads, which ran in a number of newspapers in mid-1922 promised that “Now Everybody May Exercise by Music” and stressed the ease, and the fun, of the family keeping fit together.

By the early 1920s, the term “daily dozen” had made its way into the popular culture, where it referred to any kind of setting-up exercises people could do at home.

Dozens of Daily Dozens

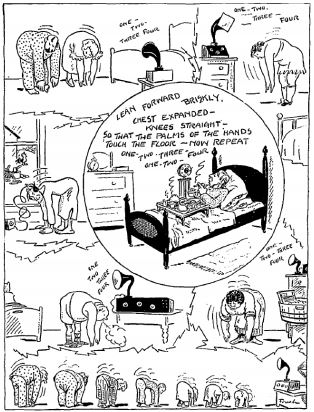

It is probably difficult for the modern reader to imagine people doing exercises by radio, but in the era before television, it was not that far-fetched.

By mid-1922, the public was relying on radio to teach everything from foreign languages to the latest dance steps, so why not use it for setting-up exercises? After all, people were regularly being encouraged to “do your daily dozen.”

Given the positive reaction (including many fan letters) that doctors experienced after they delivered radio health talks, using radio to promote exercise made perfect sense.

In late June 1922, a championship boxer from Pittsburgh, Harry Greb, went on the air via KDKA to give a health talk that Walter Camp would certainly have liked: “How to Keep Physically Fit Through Systematic Exercise.” He gave a series of these talks, but unfortunately, we do not know if he also did exercises with the audience.

We do know that sometime prior to that, probably April or May 1922, a physical trainer named Leland Bell gave similar talks on WWJ in Detroit.

There seems to have been at least one other experiment with exercise by radio sometime in mid-1922, on a West Coast station, but there are few details about which station and what type of program it was. However, one of the earliest programs where we do know that people exercised along with the host occurred in Medford Hillside, several miles outside of Boston, over pioneering station WGI.

Get Up and Get Moving!

It was on September 5th, 1922 that a unique new feature debuted.

Up until then, most health talks and exercise talks were broadcast in the evening, but this new program allowed listeners to start their day with exercise and still have time to get on with their daily activities.

The newspaper listing said “Daily Setting-Up Exercises. Three twenty-minute periods of exercise, led by Arthur E. Baird, Caines College of Physical Culture.” It was broadcast weekdays from 7 to 8 AM.

In the late teens and early 20s, as the interest in physical fitness grew in popularity, a number of schools had opened, promising to help people lose weight and feel healthier through a training regimen supervised by qualified instructors. Some of these schools augmented the exercises with hydrotherapy and massage, and seemed to be similar to today’s health clubs.

But while it is certainly true that engaging in moderate exercise on a regular basis can be beneficial, a few schools did more than tout their training regimens; they also made claims that they could cure every malady from high blood pressure to rheumatism to constipation.

Caines College (and what made it a ‘college’ is an interesting question, since its own advertisements spoke of “…open air exercises, games, diet, baths … hydrotherapy” but said nothing about courses or classroom study) had begun as the Caines Institute, Boston Medical Baths and Gymnasium. Its founder was a real doctor, Richard J.R. Caines, a graduate of Tufts College in Medford. Caines had briefly taught courses in health-related subjects at Tufts. (Tufts College had a longstanding arrangement with WGI – three of the school’s graduates had founded the station back in 1915, using the call letters 1XE, and when it became a commercial station, a number of Tufts alumnae appeared there as performers and guest speakers.)

Arthur Baird, the man chosen to host the new radio exercise show, was also a Medford resident, and the press reported he was a Tufts graduate; but like many claims he would later make about his life, this one was less than truthful. What was true was that Baird was a talented speaker. Since being hired as an instructor (and, the press reported, the head of the department of physiotherapy) at Caines College, he had done several speaking engagements around Boston, promoting the school and the benefits of exercise.

The Name of the Game: Publicity

The management of WGI undoubtedly knew of his work and thought he had the kind of personality that would inspire the public to get up early and exercise. It turned out they were right.

News about Baird’s new program was reported in a number of publications, and not just in the Boston newspapers. Magazines like Radio World, and newspapers like the Atlanta Constitution remarked on how the exercise craze had been brought to radio. The Constitution said that people all over New England were getting up early and trying Baird’s exercises.

Trenton NJ Evening Times

October 15, 1922

Unfortunately, they noted, not everyone understood what was happening. One little girl was so frightened at the sight of her mother “bending over and waving her arms” while wearing the headphones necessary for hearing the program that she ran outside and called the neighbors. Presumably, the neighbors were not busy doing exercises as well.

As for the content of the programs, twenty minutes were devoted to simple toning-up exercises that any businessman or businesswoman could use; another twenty were for people who wanted to lose weight, and the final segment was for people who were underweight and wanted to build themselves up.

Baird also explained the reasons for each series of exercises, all of which, he told the Boston Herald, had been successfully used at the Caines School for years. This regimen was especially useful in helping business executives to withstand the stresses of the modern business environment.

During the program, Baird also gave tips about diet, personal hygiene, and recreational choices, and probably encouraged his listeners to continue tuning in to WGI every morning, and to keep doing the exercises, even on the days when they did not feel like it.

Doing the Daily Dozen

In the Morning

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then Mr. Baird’s daily program soon inspired other similar programs, such as the one that began in late October on station WIP in Philadelphia.

Led by Professor William T. Herrmann of the Herrmann Physical Training Institute, it too was on the air early in the morning, at 7.30 AM, and it too promised that participants would feel much healthier from starting their day with setting-up exercises.

Another approach to exercise was heard on WBAP in Fort Worth, which began a program aimed at getting young people interested in exercise. In mid-October, Rob Roy Price, supervisor of physical training in more than 20 of the district’s schools, came up with an interesting idea. His program was a combination of talking about the benefits of exercise and then playing games that put those exercises to use in a fun way. He even devised games that incorporated Walter Camp’s “Daily Dozen.”

From Coast to Coast

By 1923, the morning exercise concept was being tried on more and more radio stations, from New York to Louisville to San Francisco.

The Y.M.C.A. absolutely did have exercise programs on the air in 1924, although, as discussed earlier, these were not the first ever or the first in North America. And the Y’s programs were not just heard on KYW in Chicago; local Y’s in other cities seemed to do their own versions.

Among the most popular was the one hosted by R.J. Horton, the physical fitness director of the Detroit Y. The morning setting-up exercises were broadcast on WWJ in Detroit, beginning in April 1924. The station’s powerful signal carried the program throughout the Midwest, generating hundreds of appreciative letters on a regular basis. The Y’s successful involvement with radio continued in 1925, and not just in the United States. Morning setting-up exercises were now being heard in Toronto at 7 AM each weekday on station CKCL, under the supervision of the Central Y.M.C.A.

Spokesmen from several organizations, including the Y, had previously given talks about what they perceived as a lack of physical fitness in the youth of Toronto; and just like in the States, the setting-up exercises on CKCL were intended to encourage listeners of all ages to start the day with some healthful activity. The program did prove to be a popular feature; it was still on the air in 1928.

The Exercise Craze Takes Off

1925 turned out to be an important one for exercise by radio.

For one thing, a major Los Angeles station, KHJ, decided the time was right for a morning exercise program, as did a major station in New York, WEAF. Both programs were extremely influential in promoting the benefits of physical fitness.

KHJ’s program began in late March 1925, and it was heavily promoted in the pages of the Los Angeles Times, which operated the station. Some articles touted the ease with which anyone could exercise by radio, while others told of the amazing results that could be obtained; there were also illustrations of active people bending and stretching as they went through their exercise routine. A typical article was headlined “Get Up Early Tomorrow and Do Your Daily Dozen with the Help of KHJ.”

In it, readers were introduced to the man who would be the host — Professor Barclay L. Severns, who had been the editor of a column about health that ran in the Times for nearly three years. Prof. Severns said that he was living proof of the good results a scientifically-designed exercise program could bring – he referred to himself as someone who was formerly “a physical wreck,” underweight and lacking in energy, until he discovered the right exercises, the right diet, and the right way to breathe. He was now taking his discoveries to the general public, in hopes that listeners to KHJ would derive the same benefits he had.

Within a week of the program taking to the air, the Times claimed that “… in thousands of homes, … sleepers jump out of bed to stand before a window [to do] the drills.” Prof. Severns’ exercise program was said to generate more fan mail than any other show on KHJ, with many requests for charts and diagrams of the daily exercises. By the time the program had celebrated its one-year anniversary, the professor had even written a book describing the methods he used and recommended.

Thanks to how far AM radio signals travelled in those days, the KHJ program boasted listeners not only in California but in Québec and Ontario, as well as a few in England. Out in rural America, farmers and their families were among the most dedicated listeners, although they wished the programs were on earlier. As one explained, he understood the 7 AM time worked for people in the cities but, for farmers, an earlier hour would mean they could exercise before going out to milk the cows and feed their other animals.

Throughout 1925, exercise programs proliferated, as did the claims of people who benefited from listening to them. One woman in Cincinnati said she had lost 28 pounds from listening to a morning exercise show on WLW. Noted author and columnist Lulu Hunt Peters again extolled the value of getting up early and doing exercises, either by using phonograph records or by participating in a radio exercise show; she said these were two of the easiest ways to make exercise a part of the daily routine.

Major Market Success

By this time, there were few major cities without an exercise program of some kind. However, the one that went on the air from WEAF in New York proved to be the most successful in terms of audience size and longevity.

The WEAF feature might not have gotten on the air had it not been sponsored – a touchy subject in those days. But thanks to the resources of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, whose president, Haley Fiske, was a strong believer in the value of physical fitness, the program was able to make an impressive debut in early April 1925.

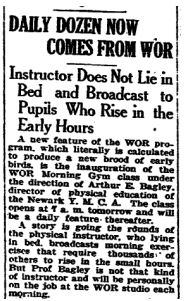

Mr. Fiske did more than just talk about the value of exercise. His company built a state-of-the-art broadcasting studio on the 27th floor of the Metropolitan Tower, and hired top musicians to provide the accompaniment for the host. The man hired to lead the radio calisthenics was Arthur E. Bagley, a former director of physical training at the Newark NJ branch of the YMCA, and a man who was already experienced with doing exercise by radio; during the past year, he had hosted a popular exercise program on another New York station, WOR, where he was reported to receive thousands of fan letters.

The Tower Health Broadcast (as it came to be known) would start at 6.45 AM, and feature exercises that were set to music. Bagley would also offer helpful hints about achieving a healthier lifestyle, while explaining how diet and exercise could lead to a longer life. Best of all for those who liked exercise by radio, Metropolitan Life was making the program available not just in New York but on a small network of stations – in addition to WEAF, there was WCAP in Washington DC and WEEI in Boston.

By 1927, the Tower network had expanded, and its audience continued to grow. One newspaper said the program was “the largest gymnasium class in the world,” and while that may have been an exaggeration, the syndicated exercise show certainly established itself all over the East. The sponsor was very much delighted with the response, and the fans kept writing in to express their gratitude, praising Bagley for his encouragement.

With a cheerful and upbeat personality, Bagley seemed to genuinely love his work. Reporters who visited the studios were amazed at how much energy he had, and even the early hour did not in any way diminish his enthusiasm. Bagley would host the Tower broadcasts for an amazing ten years, from 1925 through 1935.

Bring on the Skeptics

As with every craze, this one too began to lose its momentum.

By the late 1920s, there was a backlash developing in the medical community, as some doctors and physical therapists began to speak out about the outlandish claims certain exercise programs made. Press critics too began to ask some questions, although in that decade before radio ratings and before the advent of audience research, there was little chance of getting any answers.

Yet it was certainly interesting that in October 1925, when the exercise craze was still going strong, a skeptical critic in the New York World observed that there were now six New York stations offering morning setting-up exercises, and said it was hard to believe there was that much demand. The writer wondered if people really listened and participated, or rather, perhaps they just said they did because it made them appear to be passionate about physical fitness.

The same observations could easily have been made about Los Angeles – after the KHJ show became popular, at least three other stations came on the air with their own morning exercise programs; whether or not the public really wanted that many was not known. But it was several professors who became the biggest detractors of the exercise by radio fad.

In April 1926, Dr. Charles M. Buck of the University of Pennsylvania remarked that “early morning is the worst time for doing heavy exercise.” Buck further stated that he was thus opposed to the Daily Dozen, or any other intense forms of physical education broadcast on the radio.

Contradiction

Far more controversial remarks were made in April 1929 by Dr. Jesse F. Williams, who taught physical education at New York City’s Teachers College.

He asserted that strenuous morning workouts could actually be harmful; people were not meant to twist and contort their bodies, especially when they had just woken up. And rather than being a good way to relax, some people felt even more stressed out after they did the radio regimen, because they hurried through the exercises and then hurried off to work, leaving no time to gradually adjust to the new day.

Dr. Williams also objected to the so-called health experts who encouraged starting the day with a cold shower in addition to the exercise. He observed that many listeners believed that if a regimen was difficult, then it must have especially powerful benefits. Dr. Williams debunked this belief, saying it was foolish and lacking any solid evidence, and he criticized some of these programs for exploiting the public’s desire to find a quick and easy way to be fit.

Needless to say, Dr. Williams’ comments were greeted with scorn, including spokespeople for Metropolitan Life, sponsors of the Tower Health Broadcasts. But while some of his colleagues defended setting-up exercises (and cold showers too), others agreed with the professor that the fad had gone too far in promising magical benefits.

The Society of Directors of Physical Education in Colleges took a survey in late 1929, and found that directors of physical education at many of their member colleges were no longer impressed with the Daily Dozen. Rather, they asserted that swimming was a far better way to exercise, and that an eight-minute regimen of morning contortions was not effective in becoming physically fit.

The debate raged on, with fans of the exercise programs swearing by them; but gradually, other issues (including the Great Depression) came to preoccupy the nation far more than whether setting up exercises by radio were a useful way to spend time.

Still, from 1922 well into the mid-1930s, some of the morning exercise shows remained on the air.

In 1934, Arthur E. Bagley, host of the most successful of those programs, told the New York Times that in the years since the Tower Health Broadcasts had debuted, he had received more than two million fan letters, many of which were from places far from New York, including a large audience in Canada that received the broadcasts. 65% of the mail came from women; there was also a sizable contingent of college students.

Bagley acknowledged that he had no way of knowing how many members of his audience actually did all the exercises; many seemed to like the show’s energy, the music, and the personality of Bagley himself.

But whether the morning exercise programs had made the nation any more physically fit, or whether they just let the audience experience the concept of fitness vicariously, these programs certainly played a valuable role in promoting the importance of a proper diet and incorporating some kind of exercise into daily life.

As with the health talks, the exercise programs proved that radio was not a passive medium: under the right circumstances, it inspired people to take action, whether to learn more about health or to try to do their Daily Dozen.

Postscript:

The Mystery of Arthur E. Baird

When I began to write this essay, I quickly found the article I had vaguely recalled (the one that said exercise by radio began in 1922, rather than 1924) and, being a researcher, I decided to find out what had happened to the host of that first exercise program.

I was fortunate to have access to the Proquest Historical Newspapers database, so I did a simple search for “Arthur E. Baird.” What I found was quite surprising, to say the least. In addition to various radio listings from 1922 and the press release about his exercise program (the one with the claim that he was a Tufts graduate, which at the time, I had no reason to doubt), what came up was a court case from 1942.

It said “Professor Quiz Must Pay Ex-Wife 25,000” – a large sum back then. But what did Professor Quiz have to do with Arthur E. Baird? Quite a lot, as it turned out.

The man known as “Professor Quiz” hosted a popular radio quiz show on the CBS network. According to magazine articles, this gentleman’s real name was Dr. Craig Earl. But in real life, the 1942 article pointed out, Craig Earl was just a radio name; in reality, Craig Earl was none other than Arthur E. Baird, who had left Boston, changed his name and created a persona I would soon find out a lot about – all to avoid paying alimony and child support to his ex-wife.

By 1941, his ex evidently had put two and two together and figured out who Professor Quiz was: her former husband, who had disappeared in 1935. Now that I knew there was a connection, I did database searches for Professor Quiz, and discovered that he was a college graduate, a lawyer, Phi Beta Kappa, and an amateur magician. Back in those days, people evidently did not fact check, and many entertainers created fictional identities that the media seemed willing to believe.

Perhaps this was the case with Professor Quiz.

Digging Down For the Facts

By the time I had done this much research, I was really curious to find out what was and was not true about Arthur Baird.

I contacted the Tufts archives and found that no, he never graduated; he attended for two years and left. As for the other claims, with each telling, they got more and more amazing.

In a 1937 article, he first put forth the ‘fact’ that his name was Craig Earl. (The Earl seems to have come from Baird’s middle name.) And by 1939, he was telling the press that he was not only a doctor, but a teacher and a world traveler. By that time, he had remarried, and his new wife assisted him on his popular radio quiz show, working as the scorekeeper.

Professor Quiz told the press that he had been an orphan since he was seven (one wonders what his parents, who lived in Medford MA and were still there when he attended college, may have thought of this assertion); he said he had been raised by an uncle who was a circus performer, and who trained him in various skills while they both traveled with the circus.

And on and on it went. At some point, the former Arthur Baird actually seemed to change his name to Craig Earl, and it was under that name that he died in 1985. On his death certificate, it said he was a pharmacist.

I offer my thanks to you for reading this essay. If nothing else, it shows that things are not always what they seem. It also shows the benefits of being skeptical, whether in researching health claims or in researching the host of a radio exercise show from 1922.

– – –

Media Historian Donna L. Halper writes on a variety of radio historical topics when she is not consulting radio stations, writing books, or teaching at Lesley University, Cambridge MA.

You can contact her at: dlh@donnahalper.com