Predict the Future With Your Logs

[July 2013] Station maintenance logs are often thin. Sometimes it is because they are boringly similar. Other times, they get ignored in the pressure is to get back on the air as fast as possible. Yet, as Warren Shulz notes, good logs can be a most valuable tool.

Eventually, everything will break down. Even rocks. Certainly electronic gear cannot escape this rule.

Over my years as Chief Engineer at WLS AM and FM, I built a a series of complete maintenance logs. Using them effectively helped me to predict equipment failure before it happened rather than getting caught by surprise.

Document Things

No doubt you have heard the advice many times that it is important to document everything you do, from studio wiring to transmitter adjustments.

These logs do not have to be part of the station log. But as an engineering log, they will add up to a wealth of information for you and your coworkers on what gear works well, what gear has exhibited problems, and the best way you found to resolve issues as they occur.

At WLS, we kept a maintenance log in a text format. It was shared by our department of two. That way we both always knew what the other was working on – and how far he had gotten.

I used that file to build both a report to management showing the work load we were managing and a “failure report” to guide me in anticipating problems.

Then Use Them

The file of failure reports is an interesting tool to get a grip on your plant.

I found after a few months of data that I could predict gear failure rate intervals. Not only did it help prevent a lot of problems, but it was a great way to show the GM what a good job we did!

In general, by analyzing the logs, we were able to develop three basic reports. We broke them down quarterly:

- an overview of the status of the facilities,

- the noteworthy maintenance and repairs performed during that time, and

- the needs that were anticipated, along with the potential costs to accomplish them – and the costs if the needs were ignored.

What You Did

Any good GM will be pleased to receive an “executive summary” report that no air-time was lost during the last quarter.

If there was any lost air time, how you managed to keep such unavoidable loss to a minimum should also be welcome.

For many managers, a short discussion of the attention you gave to the station – transmitter visits, routine maintenance (parts cleaning or replacement), testing of program audio, etc, is also a valuable report – to show you are on top of things.

Actions taken to solve problems can be summarized, with a reference to the Failure Report for more comprehensive details. For example: “Problems resolved:

- Air leak to main antenna coax line was solved with a new connector installed on Heliax jumper to main antenna: see report #56

- Site total failure: see report #117

- FM Transmitter Power amplifier instability checks are complete but condition is unresolved: description under failure report #62 for ongoing work.”

The status of ongoing projects is another proper topic for inclusion. Noting which projects have been finished, which ones still are in process, and which ones need to be kick-started will tell the GM that you have everything under control as much as possible.

What Happened

The failure report takes a deeper look at what happened and what was done to reduce the chance of repetition.

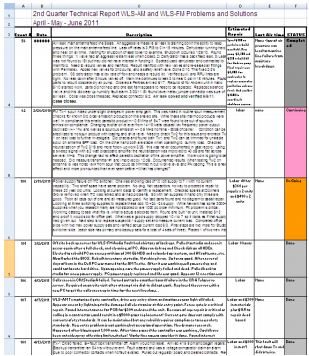

I preferred a spreadsheet format for this report, as it gave me some easy to follow columns and color-coded status notes.

A section of a failure report

What Needs to Happen

Of course, the greatest benefit of all this documentation is that it helps you to know what is likely to fail, how, and when – not always to the minute, but close enough to develop priorities in your work day.

I started with “Compliance” issues, those dealing with authorities/regulators. It was a high priority to ensure we would have no issues with government agencies. Nor we did want to allow situations to develop where an insurance company could deny coverage.

Top of the list: everything required by the FCC Rules and Regulations that apply to the stations.

Knowing, for example, the life-span of the tower beacon, I usually could schedule the re-lamping before any failures occurred.

Ditto for tower painting, tube life for tube transmitters (which also settles into a predictable range), and air filter replacements.

We also learned that if certain kinds of “event” happened that we knew would stress a transmitter, it is time to put the auxiliary transmitter on the air and start a full maintenance check. Things like that.

It’s In the Logs

Sure, a lightning strike will change everything. But 99% of the time, we could anticipate the needs of our facility – and could report that lost air time usually could be counted in seconds over a long span.

Also over time, we could use the data to build a failure trend graph, which showed that the “failure event cycle” actually had a statistical performance.

Graphing failures by incident and average

Even as the number of failure fluctuated, we could show the average remained pretty constant.

This helped GMs understand more about what we were doing – except for one GM who had the rather novel idea that “temporary transmitter interruptions is completely unacceptable” and issued a memo demanding the manufacturer fix it so it would never happen again. Fortunately, he did not last very long.

Good logs went a long way to enable our operation to make our days a lot less stressful over the years.

May your “system” of logs and their use bring similar operating successes to your facility.

– – –

Warren Shulz was the Chief Engineer for WLS in Chicago, IL for many years. Now retired in Griffith, IN, his new career is to remodel his basement when he is not out visiting family. You can contact Warren at: wshulz@cs.com